Are Men from Mars?

A brief overview of the evidence for sex differences

In my previous post I talked about the definition of sex, contrasting the biological definition based on gamete production with the definition often used by clinicians based on chromosomes and phenotypic characteristics. While the gametic definition is primary and the basis for the clinical definition, the latter allows us to clearly categorize almost all individuals regardless of fertility.

As I started writing on how I think about and define gender I realized that it’s incredibly difficult to discuss without a baseline understanding of sex differences and why they evolved. In this post, I’ll try to summarize what we know about sex differences with the hope that you’ll only have to spend 10 minutes here to get ~80% of the value I derived from a week of reading.

The biological definition of males as small gamete producers and females as large gamete producers reflects a fundamental difference in reproductive strategy by sex. This differential reproductive strategy has led to the evolution of sex differences in many species. While the nature of sex differences differs by species, in mammals there tends to be significant commonality. For example males tend to be bigger and more aggressive than females as living with my two cats has made abundantly clear…

This image was created with the assistance of DALL·E 2

Some sex differences, such as those related to physical characteristics like size and strength are relatively uncontroversial. But as soon as we wade into differences in preferences, personality, psychology or cognitive aptitudes, things get very contentious (RIP James Damore). So here’s a short summary of what I’ve come to understand about sex differences and socialization…

Sex Differences

While I never doubted the existence of some sex differences it wasn’t until I read Geary’s “Male, Female” that I appreciated how deep they really go. I, like most reasonable people, was never torn about the existence of significant physical differences between men and women, but my default assumption was that measured personality, cognitive and behavioral differences were likely the result of socially enforced gender norms rather than a natural consequence of biological differences. My priors were most likely informed by growing up in a gender-equal household, my own gender non-conformance and just maybe…feminism.

While I’m traditionally feminine in presentation I’m also high on some personality traits that are expressed more in males on average. For instance, when I took the Gender Continuum Test from ClearerThinking their algorithm was only able to make a weak prediction about my gender - favoring male. But I didn’t really think about myself this way. Instead, I assumed I was reasonably representative and that males and females didn’t differ much outside of physical characteristics…

That said, even though there’s pretty good evidence for small average differences on many traits, there’s almost always lots of overlap between the sexes. So it’s true that we can’t predict much on the basis of sex alone. However, denying the existence of these small differences leads to poor macro-level predictions. So, what do we know about sex differences?

This image was created with the assistance of DALL·E 2

Starting with the obvious - physical differences. Human males are ~20% larger than females, a size difference similar to that seen in our closest relative, chimps, but significantly less extreme than the size difference between male and female gorillas (Geary, p. 86). Males also have physical advantages other than size including higher bone density, lower body fat, greater muscle strength and power, as well as performance advantages in areas such as throwing velocity and running speed.

In primates and other mammals male advantage in body size tends to evolve through sexual selection as a result of male-male competition and female choice. Male-male competition is related to polygynous mating, in which successful males mate with more than one female. And more extreme size differences tend to be associated with more extreme levels of polygyny (Geary, p. 88). In polygynous mating systems, the variation in number of offspring is much larger for males since some males don’t reproduce at all while those at the top of the sexual hierarchy can be extremely prolific.

Evidence based on relative genetic variability of mitochondrial DNA vs. the non recombining portion of the Y chromosome suggests that we have roughly twice as many female as male ancestors which is exactly what we’d expect if our evolutionary past was characterized by polygyny. So it doesn’t seem like this is a “just so” story from evolutionary biologists. Genetic evidence backs it up.

This image was created with the assistance of DALL·E 2 which continues to struggle with feet

Despite evidence of polygyny in our evolutionary past most existing human societies are functionally monogamous. In addition, pair bonding most likely has a long history, and we see the use of one-to-one male/female “friendships” in other primates as well. Those friendships are not monogamous, but male baboons for example mate more often with and offer more protection to their female “friends” than they do to other females (Geary, chapter 3).

Given that there are obvious physical differences between males and females and that they appear to have evolved in response to differential reproductive strategies, it would be really strange if there were no associated psychological, behavioral or cognitive differences. Humans evolved to be social creatures, and we shouldn’t expect the faculties that define our social nature - emotions, theory of mind etc. - to be outside the pressures of sexual selection

One difference that is consistently observed is that males tend to demonstrate higher levels of aggression than females. The type of aggression that’s typically expressed (physical, verbal, indirect etc.) also varies by sex. Males being more aggressive on average isn’t surprising given the earlier point about how many of the physical differences between males and females evolved in response to male-male competition for mating partners.

When monogamy is either socially/culturally or ecologically enforced (i.e. when conditions are severe enough that successfully rearing children is only possible with significant paternal in addition to maternal investment) the upside from male-male competition is reduced. The high paternal investment per child expected in monogamous relationships also makes male choice and female-female competition (sometimes through explicit means like dowry provision but more typically through relational aggression) much more relevant (Geary, p. 137). In other words if relatively high status men only get to choose a single woman to have kids with they’ll be a lot more picky than they would be if they could take multiple partners.

Given how monogamy interacts with intrasexual competition the gap in aggression between the sexes is most likely narrowed rather than exaggerated by the cultural norm of monogamy. This pushes against the idea that male aggression/competition is socialized and instead implies that socialization acts to reduce male aggression while also directing it towards productive ends where possible.

In addition to aggression and other observed personality differences (such as higher neuroticism in females) there are a number of average sex differences in cognitive abilities. For example, females have higher average performance on some language-related skills and tend to be better at decoding facial expressions (which likely contributes to the idea that women are intuitive) while males outperform on some tests related to spatial cognition and mathematical ability (Geary, chapters 8 and 9).

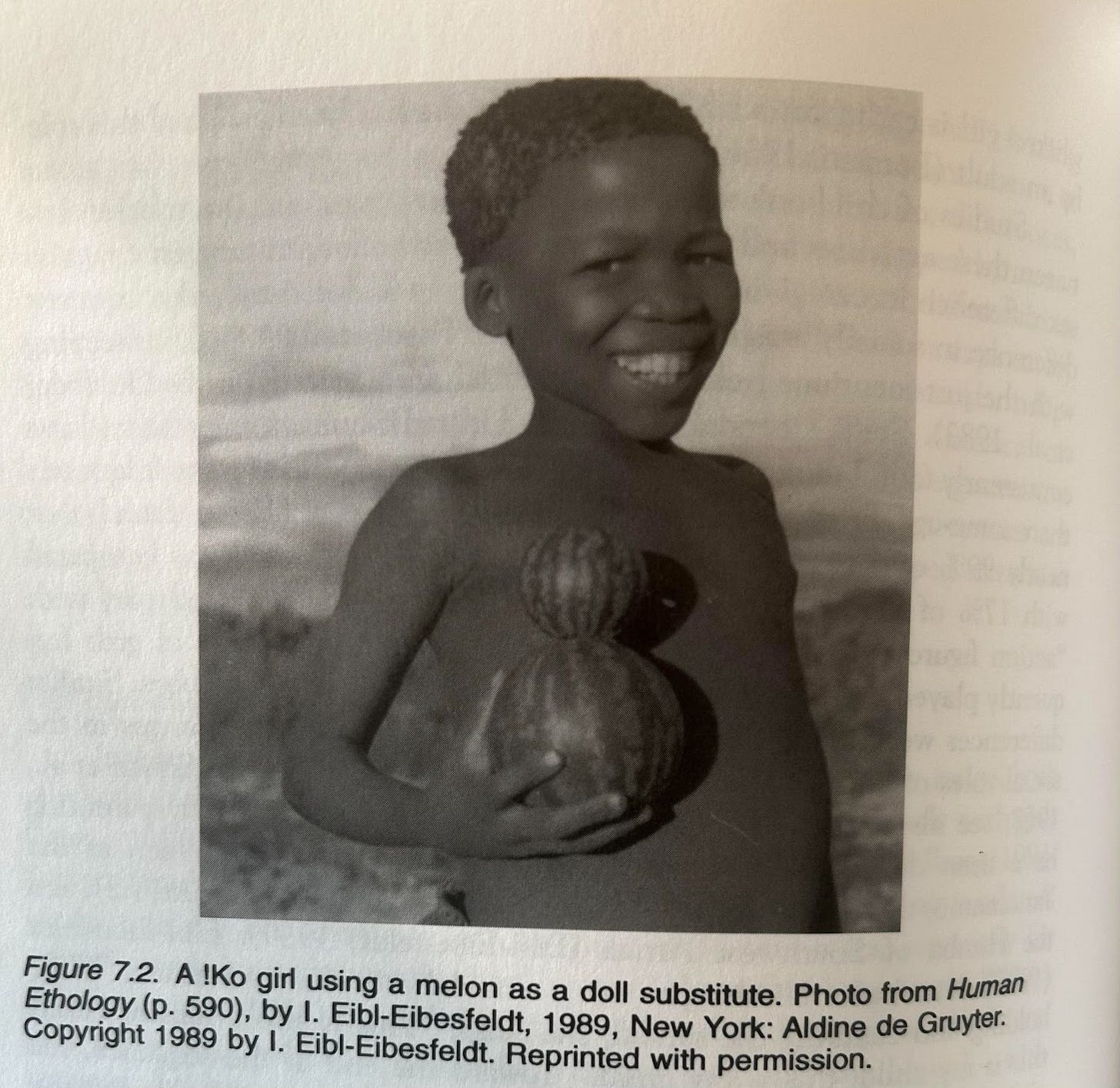

Sex differences in behavior are observed in young children, for instance boys tend to engage in more rough and tumble play while girls more frequently engage in play parenting (Geary, chapter 7). Regardless of what the Barbie movie would have you believe girls seem to naturally enjoy this kind of play.

Photo from Geary, chapter 7

These differences in play patterns are at least partially influenced by prenatal exposure to androgens and are consistent with developing the skills needed for later reproductive strategies. Males engaging in rough and tumble play can be seen as preparation for male-male competition while the much higher level of female engagement with children that we observe across cultures and in other primates lines up with a greater desire for play parenting (Geary, chapter 4).

One very important sex difference is that while males and females have very similar average IQs, men tend to have higher variance in performance across several cognitive dimensions. In other words, there are more male than female geniuses and also more “not so bright” men than “not so bright” women.

While it’s difficult to rule out socialization as a cause of sex differences, the effect of sex hormones on many behavioral and cognitive traits (including through prenatal exposure), as well as the differential reproductive strategies implied by physical sex differences, strongly imply they’re at least partially inherent. Plus, we know males and females have different levels of sex hormones and when you listen to trans women describe the experience of taking hormones they talk about cognitive and psychological changes such as a reduction of dysphoria due to the effect on their thought process and a change in the range and intensity of their emotions.

In addition, if these differences were totally or largely socialized we would expect to see a relationship between how gender equal a society is and the size of behavioral differences between the sexes. However, measures of female labor market success and the degree of occupational segregation by sex in the Nordic countries tend to be similar to those in the US despite their generous family leave policies and reputation for gender equality. There are many interpretations for the so-called “Nordic paradox”, but evidence of societies which do not have observable average sex differences is hard to find.

The general pattern seems to be something like… the average boy/girl starts off with some degree of sex-specific interests. These differences in interests lead to differences in behavior, such as a higher frequency of rough and tumble play among boys and play parenting among girls respectively. These behaviors are then often encouraged or discouraged differentially by sex. For instance, a father may discourage his son from playing with dolls or a mother may worry more about her daughter engaging in rough and tumble play and prevent her from doing so. This leads to further differences in experience as well as differences in incentives which can once again reinforce the original proclivities the individual expressed.

Note that the degree to which a behavior is reinforced differentially by sex is separate from whether the overall societal structure serves to repress the behavior in general. For example, even if we assume that parents are more likely to allow their sons to participate in rough and tumble play than they are their daughters, physical aggression is still heavily regulated in industrialized societies and the rate of violent death is much lower than in pre-industrialized societies (Geary, chapter 5).

So, overall there is strong evidence for average sex differences across a range of physical, psychological, behavioral and performance-based measures. The evidence indicates that these differences are not purely the result of socialization. As illustrated above, many sex differences are socially reinforced and potentially exaggerated but others may actually be narrowed as a result of modern social norms, as in the case of intrasexual competition for mates.

Again, I want to reiterate that there’s significant intrasexual variation and intersexual overlap on most traits so knowing someone’s sex won’t be very predictive on its own. But being aware of what is true about sex differences is crucial for correctly analyzing and diagnosing social problems.

Jokes on them because I’m already unemployed!

A decent and more than plausible summation of physical and psychological differences between the two human sexes. Or in other words, more than enough to get you deplatformed at an American university or terminated from a large corporation.