Young Mom Old Mom

When should we subsidize child-rearing?

I recently wrote about why women who want multiple kids and don’t expect to start until they’re in their 30s should consider freezing their eggs early if they can swing it financially. As I laid out, the procedure is just much more effective on average if you do it at say 30 rather than at 35. Given the (in my opinion) unattractive outcomes (shrinking economies, increasing illiberalism) that we can expect if we don’t reverse falling fertility rates, we should be incentivizing people to have more kids.

A recent post by Vidhya Mahambare on Marginal Revolution made a case for why we should subsidize child-bearing for women in their 20s. Her main point was that the later women start having kids, the harder it is for them to have multiple kids. Even if they would ideally want a second or a third baby they may simply run out of time. And as she points out the mean age of a mother at first pregnancy has increased significantly over time.

Vidhya makes a global case but I’m just going to focus on the US in this post. As shown below the mean age of a mother in the US at first birth rose from 21.4 in 1970 to 27.3 in 2021. Preliminary 2023 data (through Nov. 30) puts the average age at 27.5.

Note that the excel files used to make the plots in this post are available here, with specific files also linked below each plot.

Data sourced from the CDC National Vital Statistics Reports, and extracted from pdf format with the help of Chat GPT: Osterman, Michelle JK, et al. "Births: final data for 2021." (2023)., Martin, Joyce A., M.P.H. et al. "Births: final data for 2010." (2012). and Mathews, T. J., and Brady E. Hamilton. "Mean age of mother, 1970–2000." National vital statistics reports 51.1 (2002): 1-14. Access excel file for plot.

The risk of running out of time was also part of my argument for freezing eggs early. Even if you’re engaged at 29 and plan to have your first baby by 33 (which should be easy enough for most women to do naturally) freezing your eggs could make it easier for you to have a third baby in your late 30s, or could allow for more time between pregnancies. Additional time between pregnancies can be especially important for women who’ve had a C-section, in which case it’s generally advised to wait 18 months before conceiving again, or for women who experienced postpartum and might not be ready to go through that again right away.

While I don’t disagree that subsidizing young women having kids could be part of the solution, I’m not sure how effective it would be. Or put another way how expensive it would have to be to be effective. At least among the women I know (yes, mostly college educated) most just weren’t ready to have kids in their 20s due to some combination of the following reasons:

They hadn’t found a stable relationship yet

Hadn’t achieved financial stability

Were attempting to advance in their career in a way that was incompatible with having young kids (junior roles in most industries in North America come with the expectation that you’re ready and able to work late etc.)

They just didn’t want kids yet and were enjoying their extended adolescence

For me it was some combination of 3, 4 and (in retrospect) 1. But now that we’re in our early 30s almost all of my female friends are either having or want to have kids.

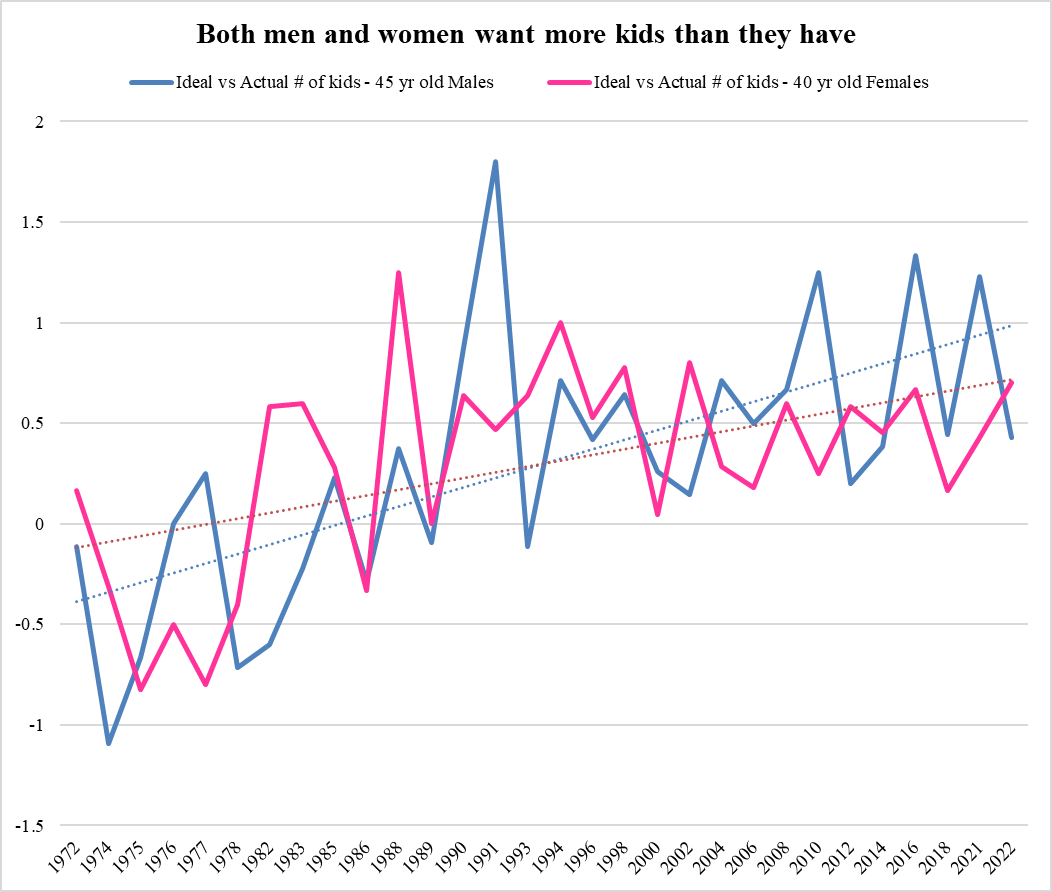

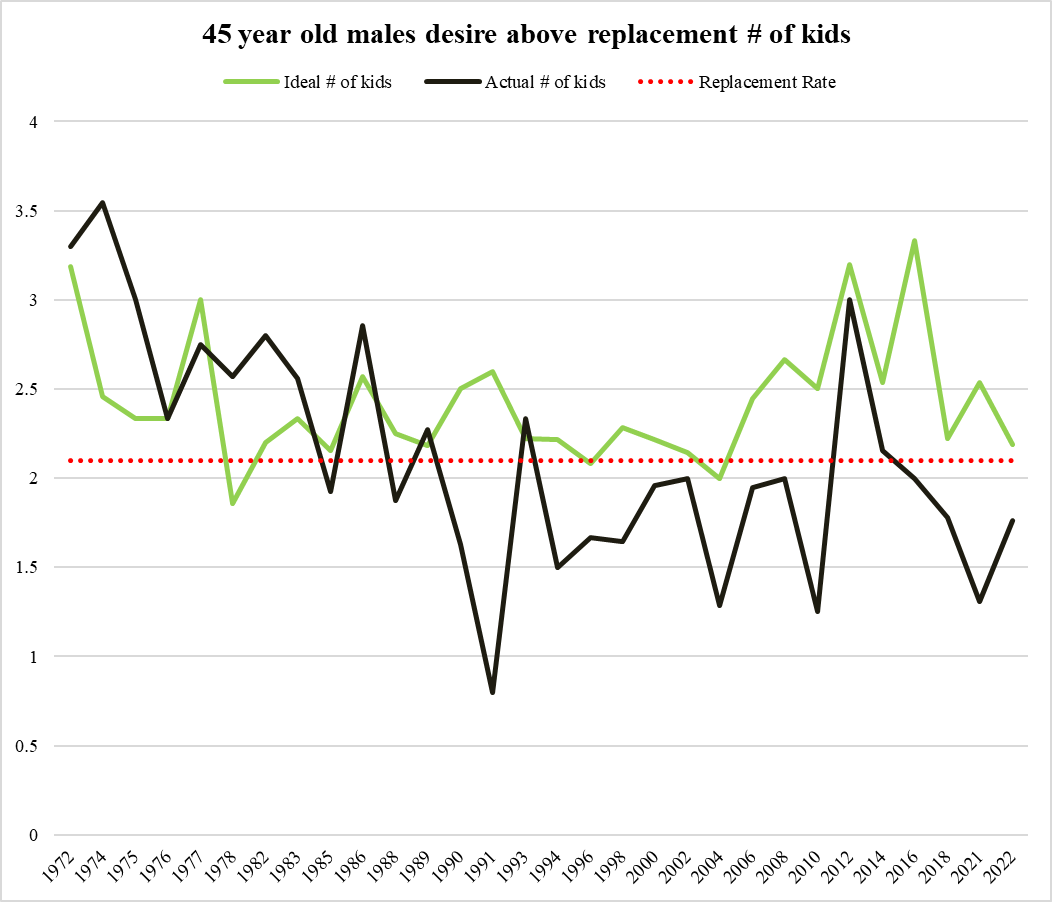

I also think that worrying about fertility is already “trad coded” and talking about incentivizing women, especially young women, to have more kids creeps liberals out, conjuring images from the Handmaid’s Tale as women’s value is reduced to their ability to “breed”. Instead of talking about how we can convince women to have more kids, I think we should first focus on making it easier for people to have the kids they want to have anyways, but for various reasons aren’t having. I used data from the General Social Survey to look at the actual vs. ideal number of children reported by 40 year old female respondents and 45 year old male respondents over time.

Access excel file for plot. Tab “plot data - ideal vs actual”.

So, according to this survey data both men and women wish they had had more kids than they have, and by 45 for men and 40 for women they’re unlikely to have additional kids. The ideal number of kids for both men and women at 45 and 40 respectively also remains above replacement rate. So getting fertility above replacement appears to be less about convincing people to have kids and more about giving them options to do so.

Access excel file for above plots. Tab “plot data - ideal vs actual”.

And if we look at the average ideal number of kids reported for all ages under 45 in 2022, we can see that young people also want more than 2.1 kids.

Access excel file for plot. Tab “plot data - ideal in 2022”.

So, now that we’ve established that people seem to want more kids than they’re having, what’s the best way to make that more attainable for them? I’d argue that encouraging more women in their 20s to have kids seems much more difficult than making it easier for older women to have as many kids as they want. As Robin Hanson lays out, culturally we’re sending a bunch of signals that are disincentivizing people from having more kids and especially from having kids young. This includes a turn away from traditional gender roles:

Fertility would be easier to increase if we had retained traditional gender roles, wherein raising kids was the primary female life role, and other work the primary male role. But our culture has decided that parenting has less potential for respect, glory, or fulfillment than other work careers, making traditional gender roles disrespectful of women. We are thus eager to signal our respect for women by encouraging them to pursue the usual career gauntlets as strongly as men, which cuts fertility. People who express concern about low fertility rates are often accused of being sexist or racist.

Louise Perry, Mary Harrington and Alex Kaschuta among others have focused on changing the narrative around motherhood, arguing that we should in fact see raising a family as high status. I think this is one part of a strategy to increase fertility, and would even say that the norm against stay-at-home-moms as it currently stands is anti-feminist. But changing cultural norms is hard and slow.

While not massively different, marriages that start in the early 20s tend to have a higher likelihood of eventual divorce relative to those that start in the late 20s or early 30s. And likely more important for child-rearing purposes, they also have a higher chance of divorce within the first 5 years. So, all else equal we’d probably rather incentivize couples in their 30s, who are in stable partnerships, to have more kids rather than those in their 20s.

Above figure pulled from: Wolfinger, Nicholas H. "Want to avoid divorce? Wait to get married, but not too long." Institute for Family Studies (2015).

One option that could help older parents reach their ideal number of children would be for the state to subsidize or pay for the cost of an egg freezing cycle (and at least one future IVF cycle to make use of those frozen eggs) for any woman between the ages of say 28 and 33, when the procedure is highly effective. To make sure the egg owners are at least somewhat invested we could have them pay half of the annual storage costs and donate their eggs if they lapsed the payment for more than 3 years.

Of course, relative to subsidizing young moms this sort of program has the disadvantage that not all eggs which are frozen are eventually used for IVF. Because we don’t want to pay for frozen eggs that end up unused, we could stipulate that program users will be expected to either pay back half the costs incurred for any eggs that remain unused by the time they’re 50, or else donate those eggs to another mother.

The ideal parameters to use for this sort of program would have to be worked out based on the expected value of the frozen eggs and the expected program usage by young women. But it would at least solve one of the main issues that prevents women from freezing their eggs when they’re at their best - most young women simply can’t afford the procedure. As I mentioned in my previous post, the median age at time of egg freezing in this large study was 38.

I started to estimate the rough cost of a program like this per marginal baby (i.e. babies that otherwise wouldn’t have been born) and it’s pretty complicated. And so is estimating the cost per marginal baby for a program that subsidizes young mothers. So for now I’ll put that aside and will post a follow-up note where I take a stab at comparing these two sorts of programs in terms of cost effectiveness and potential uptake. But for now I’d say that I’d expect it to be much easier to get women to partake in a program that extends their fertility window than it would be to get them to have babies in their 20s if they’d otherwise rather wait. As I mentioned, there are many reasons beyond financial stability that prevent women from having kids young.

The trend towards older mothers has been in place for quite a while. Below is the number of babies born per 1000 women per year separated by age group, overlaid with the total fertility rate (TFR). To calculate the TFR you take the average of the babies born per 1000 women by 5 year age group, divide by 1000 and multiply by 35 (roughly the number of potential childbearing years per woman). The TFR is calculated this way to remove the effects of a population getting younger or older from the general fertility rate (births per 1000 women of child bearing age).

First - let’s look at the long-run history:

Data sources: NCHS - Birth Rates for Females by Age Group: United States (1940-2018), Osterman, Michelle JK, et al. "Births: final data for 2021." (2023), and Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: Provisional data for 2022. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no 28. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. (2023). Access excel file for plots.

And now let’s look at the same data since 1990 - I’m excluding the teenage group as well as the over 40 groups since they’re a very small amount of overall births:

As shown above, the rising fertility rates among women in their 30s were more than compensating for lower fertility rates among women in their 20s from the mid-90s until 2008. The 30-34 rate has been pretty stable since 2008 but the 35-39 rate has continued to rise. Perhaps it could rise significantly more if more women were able to extend their fertility window by freezing their eggs young, or were able to access free donor eggs.

If we kept the rest of the fertility rates where they are now and increased the 35-39 rate from 55, where it was in 2022 to 80, that alone would increase the TFR from 1.66 to 1.79. Further, if we were able to also increase the rate for the 40-44 age group (not shown on the second chart) from 12.5 to 40 and the 45-49 years rate from 1.1 to 10 we’d have a TFR of 1.97, nearing replacement.

Finally, if we could figure out how to get the fertility rate for the 30-34 group up from where it is now (around 100) to where the 25-29 rate used to be (around 120) along with the other increases we’d get to a TFR of 2.09. Maybe we should consider subsidizing child-rearing in the early 30s as well as the 20s since growth among that age group has been stagnant for the past 15 years.

My point is not that we shouldn’t try to encourage younger women to have more kids, just that we could probably get to a replacement rate TFR by making it easier or cheaper for older women to have kids as well. And since my (surely biased) perception of what women already want indicates that it’d be easier to get older women to have more kids if only they weren’t held back by biology, and to some extent cost I think this should likely be part of any sort of mass fertility incentivization plan.

I’ll probably be back soon with some rough estimates to compare how we might think about the cost per marginal baby of programs aimed at encouraging child-rearing while women are in their 20s vs. an egg freezing subsidy. If you know of any relevant data sources please link them in the comments below!

A few thoughts:

"Of course, relative to subsidizing young moms this sort of program has the disadvantage that not all eggs which are frozen are eventually used for IVF. Because we don’t want to pay for frozen eggs that end up unused, we could stipulate that program users will be expected to either pay back half the costs incurred for any eggs that remain unused by the time they’re 50, or else donate those eggs to another mother."

I presume if we can into larger, collective programs for egg-freezing, that the scale would bring costs down, which would take diminish the financial downside.

I think the latter two suggestions would be unnecessary and unhelpful. If we're having them pay for the cost of treatments for unused eggs, that would feel coercive, particularly if they had been hoping to use the eggs and just hadn't found a partner or some other circumstance limited them. (As well, I don't think there are any other publicly funded treatments like that, whereby recipients need to repay the subsidy, at least thinking of the Canadian system?)

Donating the eggs to another mother would also feel uneasy for some; I think that would need to be done on an opt-in basis as well.

A final thought is potentially to provide the cost of egg-freezing treatments to families who do have kids naturally prior to that point, such that they receive some financial benefit as well. (This could be done in a selective way, such that it pays for education or recreation programs for the kids, as opposed to a straight financial grant.)

Have you heard the latest news out of Alabama regarding In Vitro Fertilization?