Can we afford to buy marginal babies?

Looking into Robin Hanson's numbers in light of recent culture vs. policy debates

The Debate

If AI doesn’t obviate the need for human workers and thinkers on schedule, falling global fertility could have a lot of negative consequences. There’s been an ongoing debate around how realistic it is to think that policy solutions could reverse falling fertility rates, and two pro-natalist pieces came out recently that strongly take the culture-first position. Ruxandra Teslo uses several historical case studies to argue that there’s been very limited success at increasing fertility through policy thus far and highlights some cultural beliefs that bode poorly for baby making. And Malcolm Collins argues that while enough money can of course incentivize higher fertility, any politically plausible policy would not make a meaningful and lasting difference. Malcolm concludes that religion is the answer, but probably not your grandparents religion, and suggests the need for “many experimental cultures designed to combat fertility collapse” (Malcolm and his wife Simone Collins discuss their particular experimental religion in depth on their podcast).

I broadly agree that for higher fertility rates to be sustainable in the long run cultural change, including a return to viewing children as an important part of life rather than a capstone achievement and seeing large families as high status, will be necessary. But while it’s true that recent policies intended to increase fertility haven’t been particularly effective, I disagree that centralized efforts are hopeless for creating cultural change. For example, Alice Evans talks about how “the Roman Catholic Church and Carolingian Empire stamped out cousin marriage and polygamy” in her essay on how romantic love can drive gender equality. And research by Joseph Henrich suggests that these policies led to a rise in “individualistic traits like independence, creativity, cooperation, and fairness with strangers” in the West, which persists to this day. Ruxandra might view the Catholic church as a part of culture, but during this period it was inseparable from the state and targeted policies did lead to cultural change. Regardless, the Catholic church had the threat of eternal damnation in its toolbelt and modern secular states with their terrestrial economic incentives may not be capable of the same sort of cultural control.

But then… how are we to create this cultural change? Ruxandra doesn’t really provide a roadmap, instead concluding with a mostly descriptive claim that “the fate of birth rates will be determined more by those who shape people’s attitudes, online influencers and the like”. Malcolm on the other hand calls his fellow pro-natalists to action, urging them to experiment with creating their own consistent religious frameworks. He and Simone view these frameworks as hypotheses which will ultimately be judged by their success at creating productive and plentiful descendants as he observes that “The old ways have failed us” and “raising your children in the urban monoculture with unmodified ancestral traditions is like asking them to charge a gatling gun with spears”. As an example of why existing conservative traditions are not sufficient, Malcolm cites a post by Aria Babu showing that the % of the population who believes that a mother should stay home with young children correlates with lower fertility at the country level. But I looked into this and found that this relationship does not seem to hold in OECD countries excluding Europe and that this specific belief (not just general conservatism) correlates with higher birth rates within the US, where there’s fewer potential confounders. I respect the ambitiousness and intentionality of the Collins’ family project but as Robin Hanson points out: “It is VERY hard to create new subcultures, & to have any decent chance you'll need them to be as culturally insular, including via tech averse, as these other subcultures you denigrate above.”

Raising Awareness

But neither of these pieces focus on the problem of how little the issue of the fertility crisis is known in the mainstream culture. It’s not just that people are selfishly ignoring their evolutionary duty, most of them don’t even know they have one!

UNFPA. (2022, November). Population and Fertility. YouGov. Number of adults, US: 1230, Brazil: 1015, Egypt: 1003, France: 1006, India: 1007, Japan: 1019 in Nigeria: 504

Almost no one thinks that population sizes are “too low”. Collectively, we’re still holding on to the belief that overpopulation is a major global problem. A requirement for creating the cultural change we need is to educate people about why this is a problem in the first place, and both Ruxandra and especially the Collins have used their platforms to attempt to spread this knowledge. But a lot of people don’t want to hear it. The Collins’ post arguing for demographic collapse as an important cause area on the EA forum was massively downvoted and the comments are full of unjustified accusations of racism, homophobia and more (the top comment literally starts with “I don't plan to engage deeply with this post”). This is despite the fact that the Collins are pro-immigration and think maintaining cultural diversity gives humanity a better shot at a long term future since increasing homogeneity will “lower the prevalence of orthogonal perspectives that could generate solutions to social problems which are not apparent to surviving cultures”. The Collins are also going beyond writing and podcasting; Simone is currently running for state congress as a Republican. In short, I think this is one of the few issues where “raising awareness” is actually very high value, and I appreciate their efforts even if I doubt the expected efficacy of the “experimental religions” approach.

Buying Culture (or at least time) with Fertility Policy

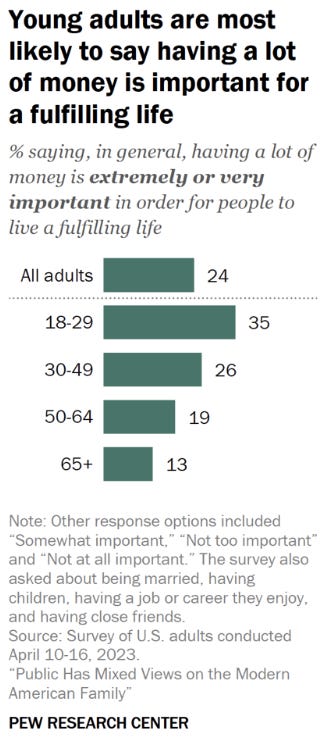

So, I take it for granted that we need cultural change. But does that mean that pushing for fertility-supporting policies is a waste of time? I don’t think so. As Robin discusses in his post We Can BUY New Culture: “this stance seems just ignorant of the history of capitalism, wherein the prospect of money and material gain has often had great influence on culture.” As Ruxandra points out, Pew survey results indicate that “young adults are most likely to say having a lot of money is important for a fulfilling life”.

If we know young people care a lot about money why wouldn’t we use it to incentivize them? One answer is that even if we could pass a policy which “works” it won’t create cultural change and fertility rates will revert to what Ruxandra calls the “culture mean” as soon as it’s removed, as they did in her example of Communist Romania. But even so, economic policy could (literally) buy us time. As Robin says:

First, subsidies would plausibly induce an earlier rise in population, from a higher min level. So less scale-dependent tech would be lost during the great innovation pause, and there’d be a lower risk of human extinction. Second, the new rising cultures are more likely to be more like the cultures of the political jurisdictions who offered such subsidies. The future belongs to those who show up, and nations who show up get more votes on future world culture.

Also, this isn’t Communist Romania, it’s the god damned U.S. of A! To make policy change plausible would require an organized attempt to build political will for such a policy. And this would involve both making the fertility crisis common knowledge and arguing for the value of children and families which I see as one secular way of pushing for cultural change.

Another answer to why arguing for policy change is a waste of time is that the size of the economic incentive that would be needed to have a real effect would not be affordable. Robin Hanson has used the size of the US national debt plus scheduled outlays for programs like social security and Medicare to argue that we should be willing to pay up to at least 300k (750k if you use the high end debt and outlays estimates) “to induce the birth and raising-to-adulthood of a single child who would then pay average levels of future taxes to repay this debt.” Subsidizing babies in units of years of federal tax payments excused would be preferable to paying a fixed amount since “if you paid this same amount to everyone, poorer folks would probably respond more strongly, though their kids would on average later pay below average amounts of taxes.” It’s hard to argue that payments of this magnitude would have no meaningful impact on fertility, but moreover Robin argues that:

The money would induce entrepreneurs, families, churches, towns, professions, non-profit orgs, and for-profit orgs to look for ways they could change their local cultures to induce more of that money to flow their way. Money can help all of them to achieve their goals, even when money isn’t their main goal.

But what I haven’t seen Robin address is that it would only be cost effective to pay these large sums for marginal babies, i.e. babies that wouldn’t have been born otherwise (although I think this is implied in his statement that we should be willing to pay these large amounts to induce the birth of a single child).

How much for a marginal baby?

In my post How much for a marginal baby? I consider the merits of a state sponsored egg freezing program and conclude that it would likely be cost effective per marginal baby (my back of the envelope estimate was around 200k per extra baby) but that even with relatively widespread adoption it would barely make a dent in overall fertility. The total fertility rate (TFR) in the US was 1.66 in 2022 and has been falling since 2008 when the increasing number of older mothers was overwhelmed by the decreasing number of younger mothers.

Data sources: NCHS - Birth Rates for Females by Age Group: United States (1940-2018), Osterman, Michelle JK, et al. "Births: final data for 2021." (2023), and Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Births: Provisional data for 2022. Vital Statistics Rapid Release; no 28. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. (2023). Access excel file for plots.

Assuming that there’s no change in fertility levels without intervention, to get the TFR up to replacement would require roughly 25% of women to have one extra baby. This means that if we paid the same amount for every baby it would only be cost effective to spend ~60k per baby (or ~150k if we use the higher estimate) since 4 out of 5 babies would’ve been born (and paid taxes) anyways. But these amounts are likely too small to incentivize the average family to have an extra kid, which means that if we did this we’d likely see a much smaller than 25% increase in fertility rates which would result in us paying way more than 300k per marginal baby. Of course, it’s not possible to pay only for the marginal babies! But it is possible to design policy that is expected to target babies that are more likely to be marginal.

As Ruxandra notes in her piece, the rate of childlessness is forecast to rise significantly, with the cohort of women born in 1992 (that’s me!) estimated to end up at around 25% childless at the end of our reproductive window. I think we can maybe shave a couple of percentage points off of that to account for the increasing trend towards later births and the advances in reproductive tech, but regardless it’ll likely be much higher than the current ~17% childless rate for women 45-50. I think we should not bother paying for first babies since attempting to economically incentivize would-be childless women to have kids would be the least cost effective for a few reasons:

Most women (~75%) are expected to have at least one baby and given the past childlessness rates I’d expect that at best we could increase that to around 85%. This means that at most 12% of first babies could be expected to be marginal, so you’d mostly be paying for babies that would’ve been born anyways.

Childless women seem more likely to have other non-economic factors preventing them from having babies. For example, it’s likely much more difficult to incentivize a woman to have a baby if she doesn’t have a good, stable partner.

Given this, I think policy should focus on incentivizing couples who would’ve had kids anyways to have more kids and should not subsidize first babies. Such a policy could start with the second baby, but since more people have two babies than have one baby it’s likely more cost effective to incentivize couples starting with the third baby, where the percentage of marginal babies can be expected to be higher. To think about the potential cost effectiveness of such a policy we have to make several assumptions. Since I don’t know of relevant survey or other data to inform these assumptions I’ve made some up to use as a starting point for a rough calculation:

I assume that people of all income levels would respond equally to a subsidy that excused them from X years of gross federal taxes per baby.

I assume that the median couple with kids would have one additional baby given a subsidy excusing them from 20 years of gross federal taxes (i.e. X=20). I came up with 20 based on responses from a few parents I know as well as Robin’s calculation that 300k = ~22 years of average federal taxes. I also cap the total value of the subsidy at a million dollars (to avoid overpaying for babies of highly successful parents who’ll likely revert to the mean) but assume that this is still high enough to incentivize 50% of parents in the top quintile (where the cap becomes relevant) to have an extra baby.

For simplicity I assume that such an incentive will induce the median couple to have only one extra baby.

I assume that 25% of women will be childless and that in the absence of policy intervention the percentage of women having 1 or more babies will decrease proportionately relative to current levels (to reflect this higher rate of childlessness). This isn’t quite right since we should expect the % of women having two or more children to decrease a bit more than this given current trends, but it’s close enough.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Fertility of Women in the United States: 2022. Table 2: Children Ever Born, Number of Mothers, and Percent Childless by Age and Marital Status, and by Nativity: June 2022

Given these assumptions and with the subsidy being awarded for third and higher-order children I estimate the cost per marginal baby at 780k (note this number was edited on 5-9-2024 to 780k from 511k as I found a calculation error on the % of babies that are marginal line within my original sheet, the updated version of the sheet is here and calc is on the “pay per baby” tab). And since I assumed that this subsidy is large enough to incentivize the median couple with 2 kids to have a third and so on, this would mean that 29% (!) of women had one extra baby relative to the orange bars above, increasing the average number of kids from ~1.7 to ~2, enough to get us basically back to replacement levels. Note that I couldn’t estimate the cost of marginal babies born to families which would’ve had 5+ kids without intervention since the above data lumps >5 into one bucket, but since this would be a small portion of the overall subsidy program it wouldn’t have much effect on my cost per marginal baby estimate. If the subsidy instead kicked in starting with the second baby, and using the same assumptions, this cost would rise to 1217k per marginal baby (again, updated on 5-9-2022 from 627k to 1217k). And we wouldn’t even need the extra babies that extending the subsidy would be expected to produce given that starting with the third baby would already be enough to get us to near replacement rates. The new distribution would be as below, in grey.

And I got my rough cost estimate based on average gross federal tax bills by quintile:

USAFacts. (2021). Average taxes paid: Income, payroll, and government transfers.

Obviously this is just a back of the envelope calculation with a lot of poorly supported assumptions, but it at least seems plausible, although certainly not obvious, that such a program could reverse fertility decline, although we’d have to take the higher end of the national debt estimates to argue this would be potentially cost effective. Whether garnering the political will needed to provide this level of support to larger families would be possible is another question. But as I said above, an organized attempt to build support for such a policy would involve both making the fertility crisis common knowledge and arguing for the value of children and families and could therefore be one part of a broader movement pushing for cultural change.

Malcolm from the article here: Thanks for writing this! This is actually a pretty good policy suggestion. (One of the best we have seen.)

That said, I don't see how it could get through congress before the situation is too critical for it to matter. Keep in mind that the 22K Korean policy only just now passed and they are at fertility def con 1 (a sub 0.8 TFR, falling 11.5% last year, and with a pop 60% over 40). If Korea can't pass something even close to what you are describing in terms of cost and fertility is a big political issue there that most people agree on how could we realistically get anything done in the US?

As you pointed out, even a mostly sane altruistic community like EA can not be convinced this is an important issue. How are we going to convince Joe Schmo? This is why we got the religion/culture rout. Not because there are not awesome ideas like the one you propose here but I don't see how we realistically change the political Overton window. (That said, we are trying our hardest and do seem to have made some headway.)

"how are we to create this cultural change?"

Given that housing is the biggest part of almost household budgets, and we can easily increase through legal changes: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21154/w21154.pdf, that would be a good place to start.

It's been a problem for decades: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Rent-Is-Too-Damn-High/Matthew-Yglesias/9781451663297 but we can and should solve it. Before we stimulate demand by giving people money, we should really increase supply.