Climate Change: The Marginal Impact of Marginal Babies

Why Halting Fertility Decline seems Unlikely to Accelerate Climate Change

While climate change may not be the primary concern driving lower fertility rates, it’s often presented as a reason to discount the problem of fertility decline. And at least some people claim it’s the main reason they don’t want kids. However, a working paper1 from researchers based at UT Austin argues that there’s little reason to expect that stabilizing the global population would lead to markedly worse climate change outcomes relative to a depopulation scenario.

The medium variant UN projection has the global population peaking at around 10.4 billion in 2086 before declining, but many people aren’t even aware that we’re on a path towards a depopulation scenario. If they are aware, they often underestimate, or simply haven’t considered, the negative expected effects that a shrinking population may have on the pace of innovation and economic growth. The assumption is often that low fertility is neutral, or even positive, because the earth is "overpopulated" anyway. Part of this is due to the general difficulty people have with intuitively understanding compounding/exponential growth, for example, in this Scientific American article (which advocates degrowth along with massive increases in government spending, without indicating where the funds for such spending will come from), they note that:

For those more worried about economics than life on Earth, the World Bank estimates that ecosystem collapse could cost $2.7 trillion a year by 2030. Deloitte recently estimated climate chaos could cost the United States alone $14.5 trillion by 2070 as we respond to the increasingly frequent and intense damage caused by extreme weather and wildfires, and the threats to communities, farms and businesses from droughts and unpredictable weather. While many assume population decline would inevitably harm the economy, researchers found that lower fertility rates would not only result in lower emissions by 2055, but a per capita income increase of 10 percent.

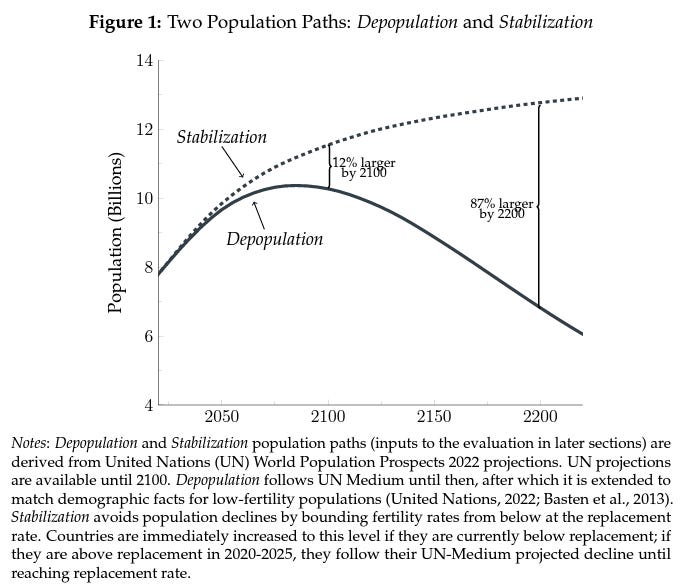

But 2055 is obviously way too soon to tally up the effects of population decline and declare it no problem! This illustrates nothing more than the obvious fact that small changes in fertility rates now won’t have led to large changes in the total population size by 2055, but will lead to very large changes in population size within a few generations. In the working paper I mentioned by Kuruc, Spears et al., the researchers plot the projected future total population under a depopulation scenario (defined by the median UN population projections referenced above until 2100 and then extended into the further future), relative to a stabilization scenario (which assumes all countries currently below replacement rate fertility immediately increase to replacement levels and countries above replacement continue on the trajectory implied by the depopulation scenario until they reach replacement rate and stabilize).

Below is their plot of total global population under each scenario, which shows little population size difference by 2055 but 87% larger(!) population by 2200:

Figure 1 from Kuruc, K., Vyas, S., Budolfson, M., Geruso, M., & Spears, D. (2023). Is Less Really More? Comparing the Climate and Productivity Impacts of a Shrinking Population.

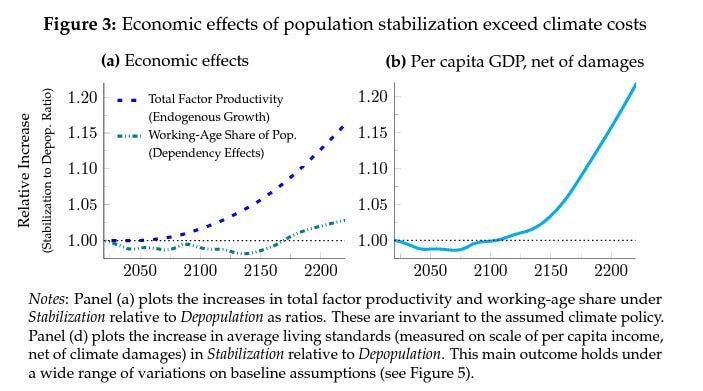

In the short term, higher fertility will result in a slightly higher dependency ratio: since children born now won’t be working for at least 20 years, the immediate labor supply will be unchanged (or if anything will slightly decrease since parents may be spending more time on childcare). With a slightly larger population and either the same size or a slightly smaller labor force, a small decrease in short run GDP per capita is expected and not at all inconsistent with expecting significantly higher GDP per capita in the longer run.

All that said, the above quote from the Scientific American article, which claimed “researchers found that lower fertility rates would … [result in] … a per capita income increase of 10 percent [by 2025].” is far higher than the small expected hit to short term GDP per capita that Kuruc, Spears et al. estimate (and which is expected based on the reasoning above). So I clicked through to their (Scientific American article) source for this claim, and it appears to be the result of their completely misreading this paper, which looked only at Nigeria(!) The authors estimated expected per capita incomes given the medium vs. low variant UN population projections for Nigeria, considering various channels through which fertility affects economic growth, including behavioral factors. Needless to say, the results from such an analysis are not reflective of the expected global effects on per capita GDP for several reasons, including the fact that even in the low variant UN scenario, the Nigerian population doesn’t peak until 2081 while the global population peaks in 2053.

But even when the potential economic effects of fertility decline are recognized, and increased immigration from low to high income countries is acknowledged to be an unsustainable source of human capital with potentially problematic implications for development within third-world countries, the risks related to fertility decline are diminished by the specter of what’s seen to be a competing catastrophic risk: Climate Change (see for instance the discussion section of this Lancet report). Even if fertility decline takes humanity down some pretty dark scenarios, they might not seem as potentially irreversible as those related to climate change. Some groups or subcultures will continue to have kids, and while the population could significantly contract, most likely bringing the state of technological knowledge along with it, we’ve come back from a Dark Age before, so why not assume we could do it again?

But if depopulation were to result in a radical decrease in economic productivity and technological sophistication in future generations, we could close the door on our chances of solving the problem of greenhouse gas emissions, and of finding ways to manage any climate-related changes which we can’t reverse. Unmitigated fertility decline could therefore prevent us from bringing about a future world which can support both a much larger population and a higher standard of living for that population into the far future.

Are climate change and fertility decline competing catastrophic risks? And which one’s bigger?

Before coming to any conclusion, we first have to question whether there is necessarily a conflict between mitigating climate change and halting fertility decline. If there is real tension between these two goals, we have to consider how we should estimate and evaluate the relative costs and benefits expected under different population growth trajectories. This is precisely the question addressed in the working paper mentioned above: Kuruc, Spears and other researchers from UT Austin and Hunter College explore how a population stabilization scenario compares to a depopulation scenario in terms of the expected level of warming and the associated climate change mitigation costs vs. the effects on GDP and GDP per capita.

The researchers present multiple scenarios and assumptions in their analysis to test the robustness of their conclusions, drawing on a wide variety of climate change scenarios and emissions per capita trajectories referenced in the relevant literature. But as someone who’s unfamiliar with population growth and climate modeling research, what was really interesting about their paper was its core argument, which was new to me but still very intuitive.

The main argument rests on a few assumptions and is summarized below:

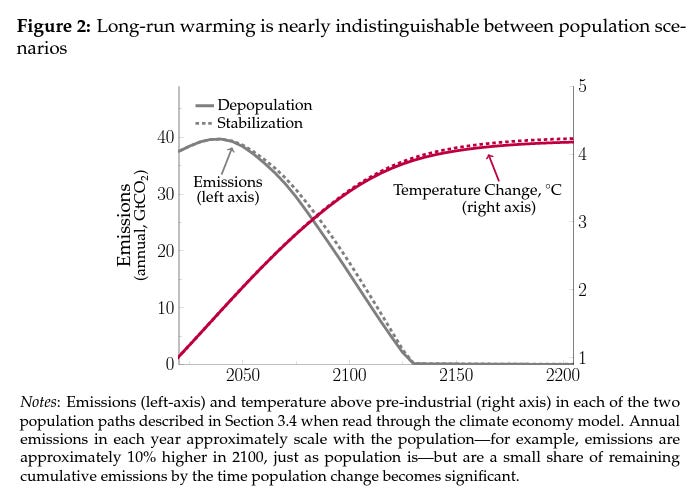

Climate change is a function of the total stock of greenhouse gasses (GHGs).

The cumulative historical stock of GHG emissions is about 50 times the current annual rate of GHG emissions, so each year of annual emissions is a significant contributor but the total stock still grows somewhat slowly.

Per capita emissions have already decreased from their peak in 2012 and are expected to continue to decrease, eventually to near 02. Note that the authors assume the rate of decline in per capita emissions is exogenous to population growth3 and do not consider the potential for negative emissions in the future.

Therefore, total annual emissions will eventually reach de minimis levels, so the difference in the total cumulative stock of greenhouse gasses will only accrue during the remaining years until we reach net-zero emissions.

Annual GHG emissions are a function of per capita emissions and total population size.

Total population size won’t be very different in the next couple of generations regardless of whether we’re in a stabilization or a depopulation scenario (as discussed above), because the exponential effects of slightly different growth rates take some time to show up in total population size.

By the time the population would be significantly larger under a stabilization vs. depopulation scenario, we should expect to have very low levels of per capita emissions. Therefore the difference in the total stock of GHGs and thus the difference in warming is unlikely to be very significant under a stabilization vs. a depopulation scenario. See Figure 2 from the paper below:

Assuming most people live worthwhile lives, and that climate change related costs aren’t so severe that this ceases to be the case in the future, having many more people living without significantly changing the climate trajectory is a big positive.

And endogenous growth models imply that this larger population would also be expected to have a higher standard of living. In the short term, a higher dependency ratio due to larger family sizes could be expected to very slightly reduce GDP per capita in a stabilization vs. depopulation scenario, but in the long run GDP per capita would be expected to be significantly higher under stabilization. See Figure 3 from the paper below:

The potential additional climate change related damages and costs under a stabilization scenario relative to a depopulation scenario are swamped by the expected GDP per capita increases, even given relatively pessimistic assumptions.

As I mentioned above, the researchers considered various assumptions around the path of emissions decline as well as for the expected economic output under different population scenarios and found that their analysis was quite robust. However, their main result—that population stabilization is unlikely to have a very large impact on the amount of global warming—depends on a simple observation. The severity of climate change outcomes depends on the total stock of GHGs, and the total stock of GHGs changes relatively slowly. If we assume that we will eventually reach a “net-zero” moment, where emissions per capita will have declined to near 0, additional people after that point will not significantly impact the global stock of GHGs. And since total population also grows slowly, the difference in the total population size during our remaining "emitting years" won't differ significantly between depopulation and stabilization scenarios, meaning that the marginal emissions before we hit “net-zero” won’t differ much between these two scenarios either, even if the long-term population sizes differ greatly.

Their work relies on assumptions about the forward path of emissions per capita, which as already mentioned are decreasing, particularly in developed countries. My understanding is that we should expect a quicker pace of declines in per capita emissions in developed countries, even though they will be declining from a higher starting point. This means that depending on assumptions about the relative pace of emissions reductions and increased development (leading to higher per capita energy consumption in developing countries) a child born in a developed country today might have lower lifetime emissions than one born in a developing country. A child born in a developed country today might also be expected to be more productive on the GDP per capita side of the ledger, and so it’s likely that the case made in the paper would only be strengthened if we assumed that a disproportionate amount of the differential population growth was from developed countries. Regardless, geographic composition effects, while interesting, would be very unlikely to affect their main conclusion. As the authors summarize in the discussion section:

Global fertility is unprecedentedly low and is continuing to fall. This has prompted concern over an aging and shrinking workforce, but also optimism about environmental benefits. Foremost among the supposed environmental benefits are reduced greenhouse gas emissions and lower levels of long-run warming. This paper shows that this optimism greatly overstates the potential climate benefits of further declines in fertility: Feasible emissions reductions resulting from changes in population dynamics are small when compared against well-studied productivity benefits of near-term increases in population growth. So population reduction is not a substitute for decarbonization policies. Moreover, reductions in fertility do not complement other efforts towards decarbonization. Decarbonization efforts reduce per capita emissions, reducing the marginal impact of declining populations and rendering future population sizes less important—or altogether unimportant, once net emissions per person reach zero.

Halting fertility decline is unlikely to accelerate climate change significantly. The potential benefits of maintaining a stable population, including for economic growth and innovation, massively outweigh what would reasonably be expected to be the marginal climate change costs due to differences in emissions. Therefore, understanding and addressing fertility decline is essential for building a sustainable and prosperous future.

Kuruc, K., Vyas, S., Budolfson, M., Geruso, M., & Spears, D. (2023). Is Less Really More? Comparing the Climate and Productivity Impacts of a Shrinking Population.

I didn’t realize this before reading their paper, but as noted in this Nature article, emissions pathways which are commonly referred to as “business as usual” in fact imply very pessimistic and increasingly implausible scenarios which represent the world as it “might have been had global emissions not slowed over the past decade” and which “do not incorporate the plummeting costs of many low-carbon technologies over the past decade.” The authors don’t consider the potential for emissions to eventually become negative, which would only strengthen their conclusion that a larger population is unlikely to meaningfully worsen long-run climate change related outcomes.

The authors don’t assume any change in the rate at which per capita emissions decline given differing population trajectories. However, depending on the speed at which progress is made in this area, it could be argued that a higher fertility rate will lead to more productive workers who could accelerate the progress on emissions reductions thereby further reducing (or reversing the sign of) the marginal impact a larger population could have on climate outcomes. Again, this consideration would only strengthen their conclusion.

The way that I tell whether someone is serious about their concern for climate change or is just using it as a rationalisation slash excuse, is to ask them if they have been on a plane in the last ten years, other than for life-saving reasons.

Nobody so far. Nobody cares enough to impose a material cost¹ on themselves. And that is what the real reason is: children are a cost, and unlike professing concern for climate change, they carry no compensating social status. You have rebutted a smokescreen. Selfish hypocrisy is the spirit of the age.

We already live in a gerontocracy. Do we want to dial it up to eleven, and watch as cities crumble around us? If not, we need to figure out a way to change society so that raising children carries a great deal of social prestige. All the practical difficulties will melt away if the prestige is great enough.

That's about the only way I can think of to improve matters,² given the zeitgeist. I have no idea how to go about it, but then I'm an INTP, barely a human at all. Maybe real humans will do better.

1. They are called "values" because holding to them can impose a material (significant) cost. Words are just words unless you are prepared to pay the cost. Carbon offset payments and the like are just modern indulgences: their cost is insignificant for most people using them, and they are lies that everyone concerned agrees to believe.

2. I have a long rejoinder to Mason Robin going into the several reasons why sub-replacement fertility in advanced countries is a bad thing, but the comments section on your essay is not the place for it. And as an INTP, I don't have the energy right now.

The best way to improve upon the impact of marginal babies is to by only giving birth to exceptional babies.