Foundational Divides

The essential dimensions of a worldview

Most of us spend a lot more time thinking about arguments for why our positions on various moral and political issues are right than we do trying to understand why our opponents refuse to internalize our obviously correct arguments. Sometimes the reason is simply that they haven’t heard our argument before, sometimes it’s that they disagree about the relevant facts, and sometimes it’s that they have different priorities in terms of what should take precedence when values conflict. When we think about it for a minute it becomes immediately obvious that the “other side” is not evil: they don’t want to destroy our society or impede (or roll back) the progress we’ve made in the direction of Utopia. They just have a different worldview. And because they have a different worldview, they disagree about what the right thing to do is.

But what do we mean by a worldview? When it comes to understanding political disagreements, we tend to rely heavily on the left-right binary. This binary does capture something important, and it can be thought of as an attempt to identify clusters of values and beliefs along which individuals differ, collectively providing a broad way to categorize people into two similarly sized groups. However, it remains woefully inadequate for capturing the nuances of moral and political views at a level detailed enough to reliably predict relevant differences with high fidelity.

These terms are also often underdefined, which opens up the arena for arguing about who is the true leftist or right-winger. You can hear many individual commentators express frustration in response to the perception that their party has shifted, moving on to supporting new and inconsistent causes, while they’ve been standing still. For instance, those who self-describe as classical liberals can be heard complaining that the woke left fails to appreciate the importance of free speech and has lost confidence not only in liberal values but in objective truth itself. Meanwhile the (increasingly rare) never Trumpers are horrified at their fellow conservatives apparent willingness to support an amoral, vulgar candidate who has no compunctions about disrespecting the most sacred of American institutions.

These individuals, who notice that they’ve suddenly been left politically homeless and don’t enjoy being out in the cold, often lament that their party is no longer their party while explaining why their views better represent the values their party is “supposed” to uphold. For example, I just read Matt Johnson’s book How Hitchens Can Save the Left, in which he argues that Hitchens’ pro-interventionist views were expressions of his consistent leftist principles. Principles which Johnson believes Hitchens upheld more successfully than many of his horrified critics, who viewed his support of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars as evidence of his shift to the right. Rather, Johnson contends that these were expressions of Hitchens’ long-standing internationalist, pro-democracy values in combination with his greater confidence in the potential of US foreign policy to advance goals related to these values.

This sort of book can be politically useful—if you’re a committed leftist and strongly prefer the overall set of policies that the typical Democratic candidate brings to the table to those of the typical Republican, but think most other leftists have badly misinterpreted how best to express your shared set of values in a particular area (in this case foreign policy), it makes sense to argue only to your in-group. But in general, it seems to me a bad use of time to worry about whether a position is left or right. And the fact that there’s a debate at all, as mentioned above, is a strong hint that there are other important binaries driving political disagreements not sufficiently captured by the left-right spectrum.

Worldviews as residing in a high-dimensional vector space

Let’s assume that at a given point in time each individual has a set of values and beliefs, whether implicit or explicit, which provide them with a general framework for understanding and analyzing specific problems and deciding what the “right” thing to do is (i.e. what is their position on a relevant issue). We’ll call this finite, but very large, set of values and beliefs their individual worldview, and assume that if we knew all the relevant factors that construct their worldview at a given point in time, we’d be able to perfectly predict their position on any specific issue.

We can think of each relevant value or belief as identifying a spectrum along which individuals vary (in terms of how strongly they agree with or oppose the value or belief). Collectively, these value/belief spectrums define a high-dimensional space in which each relevant spectrum represents a single dimension, or vector within the space, and in which each actual or potential worldview is defined by a single point. Individuals who have very similar worldviews will be described by points which are very close to each other in this high dimensional space, while those who have very different worldviews will be described by points which are far apart (as defined by, for instance, the Euclidean distance between them).

Differences in individual positions on a wide range of political or moral questions (or whatever represents the variance which you want the concept of a worldview to identify, which I’ll touch on more in my next piece) can be explained by rankings along the full set of vectors defined by these values and beliefs. Since some values and beliefs are downstream of other, more fundamental, ones and since some determine only a few, relatively unimportant positions, while others determine many, relatively important ones, it’s intuitive that some will do more work than others in terms of explaining salient differences in worldviews. It’s also intuitive that many relevant spectrums will be correlated, to various degrees, with one another, even if they also bring independent information relevant to defining a worldview.

Modeling Worldviews

In my last post I did a deep dive on the research program which produced the Big 5 personality factors. As with the concept of the high-dimensional worldview space, we can think about a high-dimensional personality space. This space is defined by the (very large) set of all personality-relevant descriptors, each of which represents a spectrum along which individuals vary. The Big 5 is then the low-dimensional model of this very high-dimensional personality space. While such a model will always fail to capture many important features of any particular personality, it can nevertheless do a reasonably good job of explaining the most salient individual differences and has been validated across multiple populations in various contexts.

We can think of an analogous project which would seek to find the Big N Worldview factors (where N is ideally somewhere between 2 and 10). The goal would be to find a relatively small number of axes which together do a reasonably good job of describing differences in worldviews across large and diverse populations, and across different times and places. These axes, or factors, would represent a simplified, low-dimensional model of the worldview space, just as the Big 5 represents a simplified, low-dimensional model of the personality space.

We’d like this model to give us a parsimonious way to describe political coalitions and to understand why they hold certain positions, and so we’d prefer that these axes map on to pre-existing, or at least intuitively interpretable concepts relevant to political ideology, moral philosophy etc. And since we’d like our model to be as parsimonious as possible, we’d want to select (mostly) independent factors, such that each represents a (mostly) distinct or unrelated worldview-relevant dimension.

Candidates for a fundamental explanatory axis

Putting aside the idea of finding a low but multi-dimensional model, we can first ask: is there a single dimension which is primary to individual worldviews. The left-right binary certainly tells us something about what defines the most important axes, but, as I mentioned above, it’s often under-defined and at least somewhat context dependent. While there are core values and themes which are consistently associated with each side, precisely what these terms reference shifts over time. Rather than identifying a clearly interpretable axis of difference, what counts as left vs. right is in part determined by what will separate individuals into two broad (and typically similarly large) clusters, such that most of the population can be roughly identified with one or the other. So what interpretable axes correlate with the left-right divide?

Progressivism vs. Conservatism

There have been various attempts to define the most significant factor driving differences in worldviews across large populations and diverse contexts. The one which is probably most familiar, given its association with the left-right spectrum, is progressivism vs. conservatism. As Rick explains in his piece Psychomagnetic Reversal:

Progressivism and conservatism themselves can be traced back to two strands within the Enlightenment heritage, epitomized by Thomas Paine and Edmund Burke respectively. Both of these thinkers accepted the Enlightenment ideal of cultural progress through the application of human reason, tempered by historical experience. There was, however, a crucial difference in emphasis.

Paine emphasized the progressive potential of individual rationality — an innovative mind breaking free from the vagaries of tradition. While Burke emphasized the need to conserve the fruits of collective rationality — the hard-won knowledge embedded within tradition, having emerged through incremental improvement of existing norms, generation by generation, and stood the test of time.

As he points out, both conservatism and progressivism as generally understood within the post-Enlightenment context imply that progress is possible, and that making progress is a worthy goal. But they disagree about how easy it is to make progress and how likely it is that you can figure out ahead of time what changes will be beneficial. And so conservatives tend to favor making slow, incremental changes, gradual enough to allow for evaluation of their impact before proceeding with larger changes.

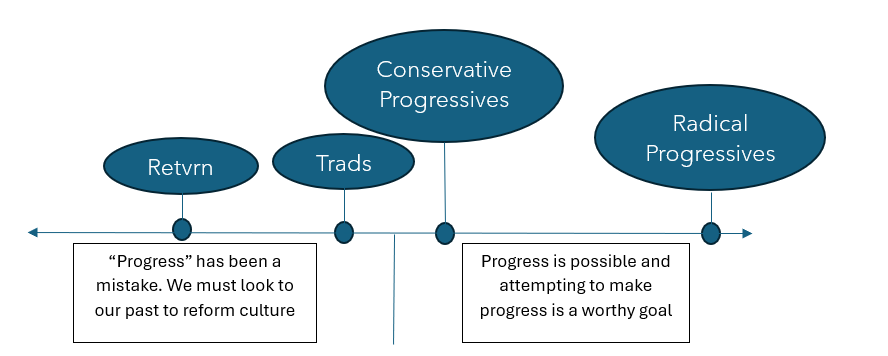

How conservative vs. progressive you are is at least in part dependent on how good you think the current system is and how bad you think alternatives can get. If you believe that we've built a surprisingly functional and resilient system—capable of producing great abundance against pretty bad odds—that the progress we've made can be lost, and that regaining it would not be easy or inevitable, you’ll probably be drawn to the conservative worldview. We can call these two groups conservative-progressives and radical-progressives and add the anti-progressives, who have recently returned to relevance, to capture the trads and retvrn set.

The constrained vs. unconstrained vision

A closely related fundamental binary is suggested by Thomas Sowell, who in his book A Conflict of Visions seeks to answer the question: “What are the underlying assumptions behind the very different ideological visions of the world being contested in modern times?” Sowell argues that two different visions of human nature—the constrained vision, which treats human selfishness as a given which social and political systems must therefore account for, and the unconstrained vision, which sees human selfishness as correctible and a product of unjust social and political systems—provides the most powerful lens for understanding broad political divides.

As he explains, individuals who hold the constrained vision tend to talk in terms of incentives and trade-offs. The focus is on designing systems (moral, economic etc.) which serve to produce desirable, prosocial behaviors and outcomes, within the constraints created by our imperfect and largely intractable human nature. The constrained vision “sees the evils of the world as deriving from the limited and unhappy choices available” and processes are evaluated based on whether they are “conducive to desired results, but not directly or without many side effects, which are accepted as part of a trade-off.”

In contrast, the unconstrained vision assumes that “foolish or immoral choices explain the evils of the world—and that wiser or more humane social policies are the solution.” Those who hold it tend to “view human nature as beneficially changeable and social customs as expendable holdovers from the past.” Those with the unconstrained vision also tend to be insensitive to the “process costs” of achieving their aims, since “every closer approximation to the ideal is preferred. Costs are regrettable but by no means decisive.” Sowell contends that these different visions lead to vastly different interpretations of our present world:

The great evils of the world—war, poverty, and crime, for example—are seen in completely different terms by those with the constrained and the unconstrained visions. If human options are not inherently constrained, then the presence of such repugnant and disastrous phenomena virtually cries out for explanation—and for solutions. But if the limitations and passions of man himself are at the heart of these painful phenomena, then what requires explanation are the ways in which they have been avoided or minimized. While believers in the unconstrained vision seek the special causes of war, poverty, and crime, believers in the constrained vision seek the special causes of peace, wealth, or a law abiding society. In the unconstrained vision, there are no intractable reasons for social evils and therefore no reason why they cannot be solved, with sufficient moral commitment. But in the constrained vision, whatever artifices or strategies restrain or ameliorate inherent human evils will themselves have costs, some in the form of other social ills created by these civilizing institution's, so that all that is possible is a prudent trade-off.

The constrained vs. unconstrained vision provides a useful conceptual framework that touches on key aspects of current ideological debates. As Sowell notes, if human nature is perfectible, then “efforts must be made to ‘wake the sleeping virtues of mankind.’” The urgent need for people to “get woke” to the unjust systems we inhabit and “do the work” to deconstruct their ingrained biases is a direct statement of this message. The constrained vs. unconstrained vision also shows up in various gender and sex related issues, particularly the debate between sex-realists and social constructionists—it’s not hard to see how the unconstrained vision is implicit in phrases like “toxic masculinity” which suggests male aggression is the product of socialization rather than something which must be tamed via socialization. It’s also possible to interpret some strands of right-wing conspiracy thinking as expressions of the unconstrained vision: the oppressive systems often cited by the woke left are here replaced by nefarious individuals or identifiable groups, but the overarching belief in a hidden structure that subjugates people remains, as does the call to 'wake up' to the malevolent forces at work.

Epistemology: Rationalism vs. Postmodernism

However, Rick, who I referenced above, suggests that the (relatively) recent epistemological shift toward postmodernism on the “woke left” reveals a more fundamental, underlying divide—one we may have failed to appreciate coming out of a period of broad liberal consensus. Describing this consensus he notes that:

Progressives and conservatives during the liberal consensus, despite what seemed in the moment to be grave differences in world-view, at least spoke the same language. They largely submitted to the same analytical standard, the one bestowed by their common Enlightenment heritage: rational argument from observed facts.

This shift on the left, he argues, has now been met with “a new force” that “has seized and transformed the right: the equally conspiracy-minded, nativist, anti-Enlightenment alt-right.” And that therefore “the deeper distinction now is not between wokists and liberal progressives. Wokism is at odds with both sides of the liberal consensus. Fundamentally it’s wokism vs. liberalism.”

Conclusion

We've explored a few contenders for the "most fundamental" axis driving differences in worldviews—from progressivism vs. conservatism to the constrained vs. unconstrained vision, to rationalism vs. postmodernism—but we haven’t yet discussed contenders for low-dimensional models more analogous to the Big 5. In the Big 5 research, the focus was on finding a small number of axes which more or less spanned the entire personality space rather than on determining a single axis which is the most “important” in the sense of explaining the highest proportion of salient differences in personality and associated behaviors. But even if we approach the question of modeling worldviews with the assumption that one axis is much more important than the others, finding what the others are, (i.e. what directions of difference does the most fundamental axis miss entirely?) is still worth doing.

In my next piece on this topic, I’ll sketch out two ways of conceptualizing the high-dimensional worldview system we’ve been discussing, specifically asking: are worldviews better understood as baskets of beliefs and values that can be combined in countless ways or as branches on a decision tree that narrows possible combinations with each choice? I also plan to discuss how Jonathan Haidt’s work on Moral Foundations relates to this project in a future post. Until then, thanks for reading!

I wonder if the left-right axis is simply out of date. The opposing teams in politics have changed several times since the 1770s from city vs farm and Whigs vs Tories, maybe its time for another change. Left vs right has worked as a shorthand for state vs market this last 100 years but this no longer seems to capture the main divisions. Certainly many people on the left have been left behind by identity politics and wokery that seemed to come from nowhere and one can hardly describe MAGA-fans as pro-market. I think the authoritarian vs libertarian has become a more significant division but the political parties have just not caught up yet.

Brilliant. No one seems to want to discuss the values conflict between left and right in detail. The disagreement between whether humans should have constraints versus whether they shouldn't lies, in my mind, at the heart of the liberal vs conservative conflict.

This is why, while I see a fair amount of baloney on the left, I'm onboard with that team. Liberalism is at it's heart a project to LIBERATE individuals from social burdens and constraints. At it's most extreme, where I reside philosophically, everyone is free to do whatever they want. Society and the state are, by definition, oppression since they constrain the individual. No constraint is tolerable. I'm not ignorant of the discord of this stance with left-wing cancel culture (which I view as absurd) but liberating individuals from constraints still places me on the left.

Right-libertarianism has it's appeal as does anarchism but both of those camps seem to have some absurd fundamental, universal concepts about how people should behave and how they would behave given a society that's unconstrained by law.

Taken to it's natural conclusion my worldview doesn't bode well for the future of humanity without the advent of robot caretakers. Still... given that my goal is the complete liberation of all individuals from the human condition I'm still doubling down. The ideal human state is where every individual is empowered to do whatever they want, wherever they want, whenever they want, for whatever reason they choose. Any other existence is simply intolerable.