Mapping the Mind

The Lexical Hypothesis and personality dimensions, from parsing dictionaries to predicting behavior

I recently participated in the evergreen debate: “what is a feminist?” I had planned to write a follow-up piece, “The Axes of Feminism”, in which I would map out some of the most relevant spectrums along which feminists disagree (e.g. sex realism vs. social constructionism). I wanted to shed light on sources of feminist infighting and demonstrate that individual feminists are members of diverse ideological movements, which evolve and come in and out of prominence over time. (That piece is still coming, but I got sidetracked—hence the post below.)

Particular manifestations of feminism may become popular at certain points in time such that you can predict someone’s views on a diverse array of subjects reasonably well just by knowing they identify as a feminist. But assuming that whatever flavor of feminism is currently ascendant defines feminism in general would be a mistake. There are always pockets of disagreement and when you take a historical view it becomes painfully obvious that feminism is not comprehensive enough to form an entire worldview. Rather, the core feminist beliefs, which I’d summarize as being actively anti-sexist and feeling that reducing sexism is an important priority, are compatible with a wide range of worldviews.

But then that got me thinking… what exactly is a worldview, or a political ideology, anyways? What are the most relevant dimensions or poles which predict individual views or behaviors across a wide range of relevant situations? What should count as a relevant situation (i.e. what sort of variance across individuals should be explained by their worldview)? And how could we go about investigating these questions without biasing the results such that the answers are predetermined?

I’m planning to explore these topics in my next free post, and then I’ll finally get back to my promised cataloging of feminist types. But to set the stage, I did a deep dive on the research which resulted in the Big 5 personality dimensions. This research was an attempt to answer analogous questions about personality to those I laid out with respect to worldviews above. And getting a deeper understanding of the approach in what is a relatively familiar example can help motivate intuitions around the purpose of, and theory behind, dimensionality reduction in general1. So, without further ado…

What is a personality?

We can think of personality as the system which predicts or determines behavior, internal states, and reactions across situations and environments as of some moment in time. We assume at least some aspects of this system are stable, or else that they evolve relatively slowly, since for personality to be meaningful requires that we can, at least to some degree, predict future actions or internal states on the basis of previous knowledge about an individual. Importantly, the domain of personality encompasses how people differ from one another—traits shared by all individuals describe human nature, personality describes human difference2.

So, our conception of personality encompasses internal states, desires, emotions, and behaviors, all of which influence one another. And there are various theories related to the general structure of this personality system, the most well-known of which is probably the Freudian model. Freud emphasized the interplay between forces that shape personality, dividing it into three components: the id, ego, and superego, which represent unconscious drives, conscious awareness, and internalized social and cultural values, respectively.

But regardless of the causal structure underlying personality, our perception of others depends on what we can observe and what they choose to reveal. Raymond Cattell, whose early factor-analytic work laid the foundations for the eventual development of the Big Five model, defined personality as “that which permits a prediction of what a person will do in a given situation”3.

While Cattell distinguished between core 'source traits,' which give rise to observable 'surface traits,' and further categorized traits as 'constitutional' (biologically driven) or 'environmental mold traits' (shaped by experience and culture)4, his approach assumed that internal psychological traits, at least those which are most relevant for personality research, ultimately manifest in observable behavior. Therefore, people who know you well are assumed to have insight into your ‘real’ personality traits.

Of course, each person is unique, and therefore, each personality is one of one5. But despite the fact that individual personalities are to some degree irreducible, we can nevertheless observe consistent patterns in how people differ. And over time, we’ve constructed language to refer to these differences, providing us with a rich set of personality-relevant descriptors6. When we say an individual expresses some common trait, we’re intuitively clustering related behaviors, and defining someone as “having the trait” if they exhibit those behaviors more often than most others do.

The Lexical Hypothesis

Since we’re a very verbal species, and since personality is important to us—being able to understand and predict behavior seems very likely to be fitness promoting in a wide range of contexts—we can assume that anything which people see as an important aspect of personality, and along which individuals differ sufficiently, will have been given a name in a personality-relevant term7. This is a core assumption of what’s called the lexical approach to the study of personality, which was the basis for research which ultimately resulted in the Big 5 model.

The size and density of the vocabulary relevant to personality (or any other category) can therefore provide information about what is most important to us, and differences across languages can similarly reflect cultural differences in focus. The fact that Inuit languages have many more words for snow than do languages developed in more temperate climates, is quite clearly a reflection of the much greater relevance of snow to daily life in arctic environments. This greater relevance justifies maintaining a much more fine-grained set of terms to refer to specific categories of precipitation which can communicate, in a single word, meanings that would require an entire sentence in English8.

Similarly, the finding that a higher percentage of German personality-relevant terms pertain to experiential states, while a higher percentage of English personality-relevant terms describe behavioral states, may point to cultural differences in focus (although this result can also be at least partially explained by quirks in the languages' lexicalization rules)9. Additionally, if you look for synonyms of personality relevant terms, you’ll find that there are more words to refer to certain broadly similar characteristics than others, possibly reflecting the greater salience of those categories.

Searching for the dimensions of personality using factor analysis

But enough with the rough overview of personality theory (which is not at all my area of expertise) and onto the factor analytic approach to studying it. Let’s say we’d like to be more precise and objective about defining and understanding personality. There are at least two broad goals related to this project:

Uncovering the most relevant dimensions along which individuals vary significantly, where relevance is determined by the ability to predict a wide range of behaviors across contexts and populations. The more behavior you can explain and the fewer dimensions you need to do it the better. And so, the goal is to find dimensions that are largely independent of one another, so that each brings personality-relevant information which the others have not yet covered. But, if this is to be practically useful you also want the dimensions you uncover to either map on to existing concepts or to reveal implicit concepts which are recognizable, and so some degree of independence can be sacrificed for the sake of interpretability. These will be referred to as personality ‘factors.’

Another goal, which is related to but distinct from the first, is to identify personality ‘types’ or common combinations of traits around which some percentage of individuals tend to cluster. You can think about these personality types as revealing identifiable archetypes which many individuals can be slotted into at least somewhat well. The better you can do in terms of categorizing individuals by type and the fewest distinct types you need to do so the better. These will be referred to as personality ‘clusters.’ I’ll explain the relationship and difference between the two goals a little later, although the evidence for personality ‘types’ is far weaker than that for personality ‘factors’.

I’m going to describe how, in working towards the first goal, personality researchers eventually developed and validated the Big 5 factors of Openness, Extraversion, Conscientiousness, Assertiveness and Neuroticism based on the lexical approach and with the use of factor analytic methods. And I’ll also briefly touch on how this relates to the second goal of understanding personality types or common archetypes.

I won’t delve into the specifics of how to go about performing factor analysis, matrix decomposition, or the particular techniques involved. Instead, I’ll focus on explaining the metrics used to measure personality, and how data was collected, as well as on conceptualizing the goal of factor analysis in this context and discussing some of the parameters relevant to evaluating potential solutions in general.

Personality as a high-dimensional vector space

The starting point is to think about all possible human personalities as residing in a very high dimensional vector space where each actual personality is defined by a single point. Individuals who have very similar personalities will be described by points which are very close to each other in this high dimensional space, while those who have very different personalities will be described by points which are far apart (as defined by, for instance, the Euclidean distance between them).

We would need a very high number of dimensions to completely define the personality space because there are so many ways in which individuals can vary, some of which are relevant and important to describing most people in a wide range of common situations and others of which are descriptive only for a smaller subset of individuals in a narrow range of uncommon situations. We want to figure out a way of determining which dimensions are most important for describing crucial aspects of most people’s personalities.

As we’ve already discussed, every individual’s personality is unique to them. But we’re a verbal species and we’ve developed a whole host of adjectives to describe specific characteristics of personality, at least approximately. Each such personality-relevant adjective10 and its antonym can be seen as defining a vector in our high dimensional personality space, where, again, each point in the space is a potential (or actual) individual personality. These vectors define a spectrum between two poles, with each one cutting a line through the personality space, intersecting the origin at the neutral midpoint between the two opposite traits.

Once again, a core assumption underpinning the lexical approach is that, since the concept of personality is very important to us, we can assume that the set of all personality-relevant adjectives in a well-developed language with a large vocabulary will cover most if not all of what we care about. Therefore, we can assume that the set of vectors defined by these adjective-antonym pairs forms a “spanning set” for the space of personality11. In other words, they will ‘cover’ (almost) all of the high number of dimensions which in aggregate define the personality space, and they will certainly cover the dimensions of personality which are most relevant or salient to us.

The assumption that our language spans the personality space is incredibly important since, if it holds, it provides us with an unbiased starting point from which to search for the most explanatory independent dimensions of personality. If a researcher was tasked with creating a personality questionnaire from scratch or with listing a set of relevant dimensions along which individuals could be ranked, it would be impossible to avoid baking in their personal biases. The questions they’d choose to ask or the dimensions they’d list would reflect their existing beliefs about the core drivers of personality, and so the results of any related analysis would also reflect those beliefs. (Previewing the next piece… if we were to approach the question “what is a worldview?” we’d want to think through what the equivalent of the lexical hypothesis for this application would be.)12

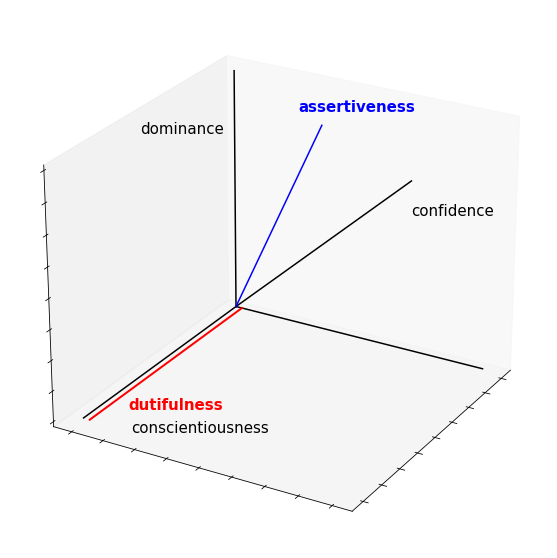

Many of these adjectives will be near synonyms of other adjectives in the set, for instance you could describe someone as being a “diligent” or “conscientious” worker without much difference in meaning. Even if we assume that there are no perfect synonyms, we could nevertheless drop many similar adjective-antonym vectors without losing much in terms of our ability to describe someone’s personality. In addition, some of these adjectives can be defined via a combination of other personality-relevant adjectives—instead of describing someone as “assertive,” you might say they’re “confident” and “dominant”. So, in vector space terms, we’d say that “assertive” can be represented as a linear combination of “confident” and “dominant”.

Below is a visualization of the sub personality space represented by only these five adjectives13:

I’ve represented assertiveness as a vector formed by equally combining dominance and confidence. And I’ve shown confidence and dominance as being related but substantially different. On the other hand, dutifulness and conscientiousness are pointing in an orthogonal direction from the other three terms, representing that they are independent of them.

Technically, while I’m claiming that a linear combination of dominance and confidence covers most of the individual difference described by assertiveness, it probably brings in some additional connotation not fully covered by these two, even when used in combination. So, to represent that, I’ve colored it blue so that ‘blueness’ can be thought of as representing the extra (but probably not very important) dimension which assertiveness brings in and which isn’t already covered by dominance and confidence. Dutifulness is shown as lying along the same direction as conscientiousness, since it’s a near synonym, but since we’re assuming there are no perfect synonyms I’ve once again used red to represent the additional (but probably unimportant) dimension of personality which this term describes.

Since many adjectives are near synonyms to one another or can be adequately described by a combination of other words, as discussed above, we could drop many of the terms in our set of vectors and still have something close to a spanning set. And if we did that for all of the relevant terms we’d be left with a set of adjective-antonym vectors which approximates a basis for the personality space. This implies that the set of vectors span the space but are also linearly independent of one another (such that they cannot be represented by any combination of the other vectors in the set).

Parsing dictionaries

So where would a researcher who wanted to study personality on the basis of the lexical hypothesis start? With the dictionary! In 1936 Allport and Odbert published their list of 17,953 words “descriptive of personality or personal behavior” from the 1925 edition of Webster’s New International Dictionary14. Since personality describes human difference, as mentioned at the outset, they focused on terms that describe and differentiate individuals:

The criterion for inclusion consists in the capacity of any term to distinguish the behavior of one human being from that of another. Terms representing common (non-distinctive) behavior are excluded, e.g., walking and digesting, whereas more differentiating and stylistic terms applied to these same activities, such as mincing and dyspeptic, are included. In many cases the application of this criterion involved a considerable degree of arbitrariness. In deciding doubtful cases the dictionary definition was followed: if in any of its meanings a term might be differentially employed in characterizing personal behavior it was admitted.

They separated these terms into four categories:

Personal traits: Those that “symbolize most clearly "real" traits of personality. They designate generalized and personalized determining tendencies—consistent and stable modes of an individual's adjustment to his environment.”

Temporary states: Those that “characterize a person's mood, emotion, present attitude, or present activity (but not his enduring and recurring modes of adjustment)”

Social evaluations: Those that are evaluative, which would affect whether we “judge a man as worthy”

Metaphorical or doubtful terms: Basically, all those that don’t fit into the three prior categories.

Constructing Cattell’s basis from Allport and Odbert’s spanning set

The first group of Allport and Odbert terms, containing 4,504 words that “symbolize most clearly “real” traits of personality,” went on to form the starting point for the first systematic factor analyses related to personality, performed by Raymond Cattell. His 1943 paper15 describes how two judges—“one a psychologist, one a student of literature”—reduced the original list of 4,504 terms with some additions and subtractions (the spanning set), to 171 trait clusters (the basis), by grouping near synonyms and, where appropriate, their opposites16, comparing their results, and discussing further in the relatively few cases of disagreement:

After the work of classification had proceeded for two or three months it was found that the two workers were converging toward very similar synonym lists, both with regard to the number of categories, which seemed likely to approximate two hundred, and with regard to the disposal of particular words. But it was also found, and particularly where there were disagreements, that the categories in fact sometimes passed continuously one into another, in one or more directions. The term "surface" was thus seen to be more than a metaphor, for in these cases it became necessary to carve the categories by arbitrary incisions out of an area of evenly distributed terms. At this point, the judges and other psychologists were brought together for discussion of the situation. In this way it was usually found that some natural nuclei for categorization suggested themselves and were generally agreed upon, so that finally a single list of categories emerged and one in which everyone agreed on the place assigned to particular words.

They found that the number of synonyms in each category varied significantly, “[f]or example the synonyms clustering about the key word "talkative" numbered 48, those in the category of "frank" numbered 24, and those under "clever" only six.” This variance in the number of terms per category could be interpreted as reflecting the relative importance of each category, if we assume that more words are developed to describe attributes that are most salient to us, or most predictive of other attributes (as with the number of words the Inuit have for snow). Regardless, Cattell notes that:

[T]hat there are reasons other than utility and necessity accounting for the prolificness of language in particular personality areas is well illustrated by, for example, the perennial coining of semi-slang terms for "intoxicated" and for "impecunious." Having regard to our main purpose, therefore, we decided not to make further investigations of these differences of synonym frequency, considering them irrelevant to the question of factor space.

But while a massive improvement on the more than 4000 terms they started with (assuming this smaller set of distinct terms is still able to more or less span the full personality space), 171 terms is still a lot! So, they collected data from a relatively small sample of 100 individuals, each of whom were rated by an acquaintance as to whether they were above or below average on each of the 171 traits. Correlations across trait ratings were calculated using the resulting data set and these “were set out for inspection on a table 14 feet square” with the aim of identifying commonalities across trait clusters in order to further reduce the set of categories so that larger analyses could be performed in the future17.

As an aside: I encourage you to reflect with gratitude on how the glory of modern computing has saved us all from having to analyze correlation matrices by observing them on giant 14’ square tables!

The final result was a set of 60 clusters, grouped based on the sample of individual’s scores being at least 45% correlated with all other items included in the cluster. These 60 clusters included 147 of the items in the original trait list, and so were assumed to safely cover most of the descriptive space formed by the original 171 terms.

Cattell’s factor analysis

Cattell then used this set of terms to perform a larger survey and factor analysis, the results of which he published in 194518, but had to cut them down once more before beginning to get a relatively manageable set of 35 clusters on which individuals could be ranked19.

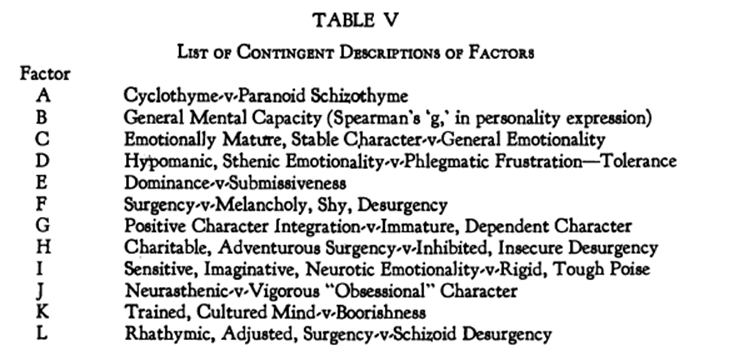

Cattell went on to recruit a group of 208 men20 from a variety of backgrounds organized in groups of 16 members each. For each group, two judges, both of whom were longtime acquaintances of the individuals in that group, independently ranked the participants as to whether they were above or below average on each of the 35 trait clusters. This formed the data set for his larger factor analysis, which resulted in the below set of 12 provisionally named factors:

I sure would love to see someone in HR explaining to an employee that they were scored as “boorish” as opposed to as having a “trained, cultured mind” on the workplace personality test.

Reviewing the objectives of a personality factor analysis

But what are the conditions which we would want a factor solution to ideally meet?

Once again, we can imagine that the range of possible personalities is represented by a high-dimensional space spanned by the original set of adjective-antonym pairs, with each point corresponding to a particular personality profile. The goal of factor analysis is to reduce this high-dimensional space by identifying patterns of correlation among the variables, allowing us to define common sources of variance that can predict multiple related traits.

It's certainly intuitive that many personality traits are related—someone who’s described as ‘talkative’ would often also fit the description of being ‘gregarious’ or ‘friendly.’ While each additional personality-relevant term may add a subtle, independent nuance (since even near-synonyms have slightly different connotations and usages), many terms clearly cluster around the same core trait, as discussed above.

If you were tasked with choosing just three terms or trait clusters to use which would allow you to describe the maximum breadth of personality differences, you surely wouldn’t select the set defined by: ‘gregarious,’ ‘talkative,’ and ‘friendly,’ because they all point to the same underlying trait: Extraversion, as defined in the Big Five model. (This trait is probably closest to Cattell’s surgency vs. desurgency, labeled as "Factor F" above). Instead, you’d want to select terms that describe distinct and highly salient aspects of personality—traits that are mostly independent of one another—so that each term adds new descriptive power, uncovered by the others.

Therefore, the goal of factor analysis in this specific context is to identify a set of mostly independent dimensions (or factors) which explain as much variance in individual personalities, as measured by ratings on the 35 trait clusters, as possible. These factors should also map onto interpretable, if not pre-existing, concepts related to personality. The hope is that the structure of the correlation matrix derived from the data will reveal a manageable number of distinct personality dimensions21, which in combination are predictive of many more specific traits or behaviors (such that it’s possible to describe a meaningful proportion of individual difference using only these factors), and which correspond to “the 'real' traits or factors underlying the correlations”22.

As I said earlier, I won’t attempt to explain the specific methods used to arrive at factor solutions, but hopefully I’ve clarified the general objectives we’d like such a solution to achieve: it must identify a manageable number of dimensions that span a significant portion of the space, such that they are useful in predicting variance along a wide range of other dependent variables, these dimensions must therefore be mostly independent of one another to avoid redundancy, and they should correspond to real, interpretable unities rather than to superficial or spurious associations that do not represent meaningful shared variance.

Factors vs. Clusters

I want to briefly revisit the distinction between personality ‘factors,’ which we’ve been discussing, and personality ‘clusters’, which I mentioned earlier. Personality ‘clusters’ are distinct from personality ‘factors’ and refer to common combinations of these mostly independent traits that can be identified in various populations, allowing us to recognize personality types relevant to a significant proportion of people.

We haven’t yet gotten to how later researchers developed the Big 5 model on the basis of Cattell’s factor analysis and trait clusters, but I’ll reference that factor solution since it’s familiar to most people. As mentioned earlier it includes: Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Openness. Following the description in the 2018 Gerlach et al. paper23, which analyzed several large Big Five datasets to with the aim of identifying stable personality types, one way to think of clusters is as being “centered in regions [of the personality space] where we observe a substantially larger fraction of respondents than expected from a random null model”.

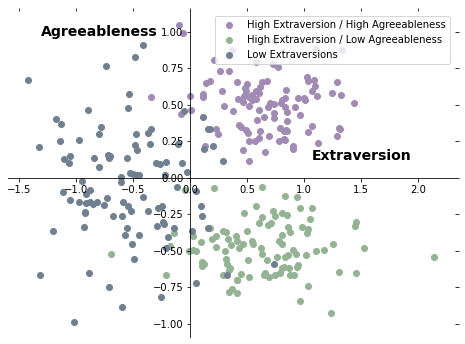

Even though the factors are largely independent, it's still possible to observe non-uniform patterns in how people’s scores cluster together. For example, imagine that extraversion and agreeableness are almost entirely independent of one another, such that individual scores across a population on these dimensions are uncorrelated, but that among highly extraverted people there are two distinct clusters of those with high vs. low agreeableness. If this were true, the profile of scores on these two axes might create three distinct clusters, such that they could be seen in a plot of (simulated) data meant to reflect individual scores along these two axes24:

The above is for illustrative purposes only, and I won’t delve into personality types or the evidence for clusters which define them any further, but hopefully this helps to make clear the distinction between the search for factors vs. the search for clusters.

Building on Cattell and validating the Big 5

Cattell later analyzed similar data for a group of male students and was able to largely confirm the general factor structure he had found in his initial study25. He then also extended his analysis to a sample of female students and again found factors which he described as “overwhelmingly similar” to those found in the male data26.

In 1961, researchers Tupes and Christal re-analyzed two of Cattell’s data sets, as well as two data sets from another researcher, Fiske, who had carried out a similar analysis to Cattell’s in 1949 (but among individuals trained in clinical psychology, with longer assessment periods and with more fine grained assessments on each relevant measure) but the results of which were difficult to compare to Cattell’s27, and four additional sample data sets they collected from groups in the Air Force28.

They found that “[i]n each analysis five fairly strong rotated factors emerged” which they termed: Surgency (or Extraversion), Agreeableness, Dependability (or Conscientiousness), Emotional Stability (or low Neuroticism) and “Culture” (probably close to the Big 5 Openness factor) which they described as “the least clear of the five factors identified by the eight analyses”, “defined by the variables Cultured, Esthetically Fastidious, Imaginative, Socially Polished, and Independent-Minded”.

This five-factor structure was replicated by Warren Norman in research published in 196329. And later work by Costa and McCrae in the 80s found that self-report questionnaires could also be used to measure Big 5 personality dimensions. To test this they collected self-report questionnaire data from participants in addition to peer ratings on trait clusters (once again validating the five factor structure found by previous researchers) and their results showed that self-reports and peer ratings showed substantial agreement30. Later research has found that the Big 5 measures are also predictive of outcomes across a range of domains including in job performance31, important life events32 and academic success33.

The reason people differentiate the Big 5 as being ‘more real’ or ‘scientifically supported’ relative to other sorts of personality classification methods is because the general model has been successfully replicated across a wide range of sample populations and domains. And the decades of research related to the Big 5 has validated that the lexical approach combined with factor analytic methods appears to have been able to successfully identify stable traits which predict significant variance in personality ratings, behaviors, and outcomes across diverse populations.

If you’re still with me I hope you enjoyed this long romp through the history of the Big 5, or at least have a slightly improved intuition for the goals of factor analysis in such a context. I’ll be revisiting these concepts again in some upcoming pieces, but until then thank you for reading and if you enjoy my writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber, I so appreciate it!

Note: this intro was added on 10/20/2024

Both of these details are captured by the Handbook of Personality which states that “[p]ersonality refers to enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that distinguish individuals from one another and that can predict their responses to the environment."

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Cattell, R. B. (1950). Personality: A Systematic, Theoretical, and Factual Study. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cattell, R. B. (1945). The description of personality: Principles and findings in a factor analysis. The American Journal of Psychology, 58(1), 69–90. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1417576

While we can notice similarities and differences which are highly salient and relevant in a range of situations, there’s no reason to believe there *actually* exists some finite set of platonic common traits from which all human personalities are constructed, with each of us having some particular subset endowed in varying amounts. Regardless, modeling personality as if this were true is possible and useful.

These descriptors can refer to internal states as well as observable behaviors or attitudes—in Freudian terms, they might correspond to elements of the id, ego, or superego. Yet, since our understanding of someone’s internal state ultimately relies on observable behavior, when we use these terms to describe others, we’re primarily referencing their personality "phenotypes" rather than "genotypes" as suggested in:

Saucier, G., & Goldberg, L. R. (2001). Lexical studies of indigenous personality factors: Premises, products, and prospects. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 847-879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696167

Saucier, G., & Goldberg, L. R. (2001). Lexical studies of indigenous personality factors: Premises, products, and prospects. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 847-879. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696167

Footnote added on 10/20/2024: as one commenter suggested, word use frequency would probably be a much better metric of relevance, since there are many contingent reasons for word count differences which are not related to conceptual importance, but all else equal it still seems intuitive to me that word count tells you something about salience.

Angleitner, A., Ostendorf, F., & John, O. P. (1990). Towards a taxonomy of personality descriptors in German: A psycho-lexical study. European Journal of Personality, 4(2), 89–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2410040204

Not every personality relevant term is an adjective, but the list of terms from Allport and Odbert, which Cattell based his work off of, were largely comprised of adjectives, so we’ll use that as shorthand for all personality relevant terms.

A spanning set is a set of vectors which through linear combinations can describe the entire space, which means that they could be combined to point at any point within the space. In this context the lexical approach assumes that the language we have to describe personality is sufficient to describe any possible personality sufficiently well by combining in various ways elements from our set of personality-relevant terms.

Note: above paragraph was added on 10/20/2024

I’ve only shown the positive directions of each as to not complicate the visual, but you could picture each adjective vector going through the origin in the opposite direction as representing the antonym of each adjective shown (or its negation). I should also note that not every adjective has a clear antonym, so it’s possible that some may be better represented only by a positive scale, such that individuals differ as to whether and how much of the trait they express, rather than based on which side of an oppositional pole they’re on.

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47(1), i-171. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093360

Cattell, R. B. (1943). The description of personality: Basic traits resolved into clusters. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 38(4), 476-506. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063096

Cattell notes the desirability of defining opposites, but also the difficulties which can arise and the approach taken:

For the sake of parsimony and simplicity we classified with synonyms also opposites. This resulted in the great majority of trait categories being "bipolar" traits. The further advantage then arises that in rating, and other operations upon traits, more accurate orientation of the trait occurs than if only one end of the axis were defined. The fixing of opposites also compels the experimenter to sharpen and refine his concepts and the rater to concentrate on the essential nature of the trait he is dealing with.

Nevertheless, bipolar definition is fraught with dangerous logical and psychological pitfalls. Any trait term will be found to have a variety of opposites, according to one's field of reference. To illustrate by a physical example, the opposite of the north pole may be the south pole, or the equator, or any nonpolar point on a sphere. In psychological matters the universes of reference may be even more inexplicit. Is the opposite of bullying, sadistic, etc., to be considered as just nonbullying or as protective or as masochistic? Is creative the opposite of sterile or of destructive? Is impulsive the opposite of self-controlled or of phlegmatic? Some opposites are logical rather than psychological; some have reference to native factors in behavior, others to metanergic (9) or other factors determining the same kind of behavior.

Our procedure here, following the arguments of the preceding article, was to deal with psychological rather than logical opposites, aligning opposites with regard to the real dynamic, constitutional, and social mold trait (n) structure, as far as structure can at present be known.

From Cattell on reducing the 171 clusters:

Our next purpose, [...] was the further reduction of this list, through strictly correlational methods, to a set of variables brief enough to permit their being very reliably estimated and completely factor analyzed with the time and facilities possible to one experimenter.

The preliminary correlational reduction was made on correlations based on ratings on 100 adults, each rated by an intimate (but not emotionally involved) acquaintance, on the 171 traits obtained by semantic reduction. The rater was required to make a judgment only as to whether the subject was above or below average on the trait, i.e., whether he was best described by the right- or the lefthand member of each pair, e.g., whether ascendant or submissive.

[....]

The correlations having been computed, by the use of Thurstone's diagrams (46), they were set out for inspection on a table 14 feet square. Our objectives were now two: (1) to discover the cluster structure among these variables, as something distinct from the factor structure which would later be revealed, and, (2) to choose from the 171 variables a set of some 30 to 40 derived, representative, variables which would contain, if possible, all the factors involved in the larger trait population. This second step might or might not be identical with the first. Only if the clusters included all 171 variables and were sufficiently small in number would it be possible to take the clusters as the new variables for the intensive factor analysis.

Cattell, R. B. (1945). The description of personality: Principles and findings in a factor analysis. The American Journal of Psychology, 58(1), 69–90. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1417576

From Cattell on reducing the ~60 clusters down to 35:

Through lack of funds for so extensive an undertaking, it became necessary to reduce the clusters found above to a shorter set. This reduction was accomplished by (a) neglecting some five or six of the smaller, less reliable clusters, (b) using a single 'nuclear' cluster where two or three of the clusters had extensive overlap, and (c) using from the remaining clusters only those already confirmed by other researches. The degree of confirmation of our clusters is set out and discussed elsewhere. These condensations resulted in 35 clusters, as listed in Table I. Naturally a factor analysis of these cannot be guaranteed to contain all the factors present among the original 171 traits of the personality sphere; but the analysis is likely to contain most, and they will at least be those which give the major perspectives of personality and account for the variance of the greatest number of traits.

While Cattell made a concerted attempt to select men from varying class backgrounds he decided to restrict the analysis only to men for reasons that aren’t entirely obvious to me. If the goal was to fix some of the personality traits that emerge as a result of different environmental conditioning you’d likely want to restrict the sample to a single class as well. Restricting to individuals exposed to “male conditioning” only seems to carry the risk of failing to recognize important types of variance which may not show up as important (in terms of describing individual difference) among a sample of only males. If we want to understand the drivers of personality that remain predictive across a range of contexts rather than overfitting to a particular sample it seems like including both sexes would be necessary. However, it may have been decided that analyzing a single sex sample at a time would avoid mistakenly identifying spurious factors. As Cattell explains: “All Ss were of one sex (male) to avoid complications in rating and in extraction of such factors as would result from lack of sex homogeneity, but they were otherwise as representative as possible of a full population-range of personality and background.” In later work Cattell extended his analysis to a female sample and claimed to find a very similar factor structure.

Each of these dimensions or factors can be represented as a linear combination of the underlying trait clusters, with the weights (or factor loadings) indicating how much each cluster contributes to the factor. Individuals’ scores on trait clusters in combination with the factor loadings determine how they score on the factors. Each trait cluster can also be represented as a linear combination of the factors.

More from Cattell discussing the particular factor rotation he was looking for, from:

Cattell, R. B. (1945). The description of personality: Principles and findings in a factor analysis. The American Journal of Psychology, 58(1), 69–90. University of Illinois Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1417576

Of course, if the psychologist required only a set of mathematical predictor to replace the numerous battery of variables entering into a particular correlation matrix, his choice of factors could be made quite arbitrarily, for one set is practically as efficient as another and all have equally the virtue of offering decidedly fewer major factors than there are test-measurements. Psychological research as such cannot, however, be content with this limited objective, and the present study was undertaken with scientific aims beyond those of psychometric economy. Its aim was to discover the outlines of psychologically real traits. Indeed the decision to use the factor analytic method was made because general and clinical analysis led to the conclusion that the functional unities which we call source traits will manifest themselves as factors. The problem therefore presents itself of finding, among factor-analytic solutions, the particular system and the particular rotation which will define factors corresponding to the one psychologically real set of functional unities, i.e. the 'real' traits or factors underlying the correlations.

Gerlach, M., Farb, B., Revelle, W., & Amaral, L. A. N. (2018). A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(10), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0419-z

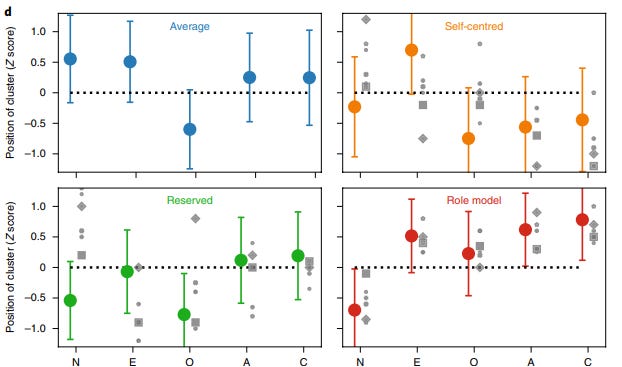

They find four clusters, which to varying degrees map on to those found in earlier research:

The least robustly identified cluster [...], which we denote the ‘average’ type, is characterized by average scores in all traits [...]. The remaining three clusters can be roughly organized along the two dimensions of neuroticism and extraversion. One of the most stable clusters [...], which we denote the ‘role model’ type because it displays socially desirable traits, is characterized by low scores in neuroticism and high scores in all other traits. [...]. By contrast, the two other clusters are characterized by traits that are less socially desirable when compared to the characteristics of the ‘role model’ type. One of the clusters is marked by low scores on openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness, whereas the other cluster shows low scores on neuroticism and openness.

The average and standard deviation of scores for individuals identified with each cluster are plotted above, where the letters at the bottom represent Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness respectively.

I didn’t attempt to make an illustration that reflected real clusters, since the research in that area is less developed and the existence of real personality types is much less clearly validated by data analysis. The first paper below is one place to start if you’re interested, it uses a data-driven approach to analyze large samples of Big 5 scores. The classic papers in this area, which have been critiqued for method and sample sizes used, produced types referred to as the ARC personality types (“named after the authors of the seminal studies by Asendorpf et al., Robins et al. and Caspi et al.”). These sources are also below for reference:

Gerlach, M., Farb, B., Revelle, W., & Amaral, L. A. N. (2018). A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(10), 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0419-z

Asendorpf, J. B., Borkenau, P., Ostendorf, F., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: Confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults. European Journal of Personality, 15(3), 169–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.408

Robins, R. W., John, O. P., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1996). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled boys: Three replicable personality types. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.157

Caspi, A., & Silva, P. A. (1995). Temperamental qualities at age three predict personality traits in young adulthood: Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Child Development, 66(2), 486–498. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131592

Cattell, R. B. (1947). Confirmation and clarification of primary personality factors. Psychometrika, 12, 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289253

Cattell, R. B. (1948). The primary personality factors in women compared with those in men. British Journal of Psychology, 39(1), 114–130.

Fiske, D. W. (1949). Consistency of the factorial structures of personality ratings from different sources. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 44(3), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0057198

Tupes, E. C., & Christal, R. E. (1992). Recurrent personality factors based on trait ratings. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00973.x

In which they provide more context on the research they were building off of:

Cattell (1945, 1947, 1948) has published two factor analyses of men and one of women, each based on ratings of 35 personality traits selected to represent the entire personality area. In each he found 11 or 12 factors which he has identified as similar in the three analyses. For many of these factors, however, the factor loadings are so small that some factor analysts would hesitate to try to interpret them at all. Fiske (1949) analyzed ratings of 22 of the same or highly similar variables using beginning graduate students in clinical psychology for his sample. He obtained about the same factorial structure from ratings of the students by themselves (self-ratings), by their peers, and by clinical psychologists. However, a comparison of the factors isolated by Fiske with those defined by Cattell is quite difficult, in spite of the fact that the variables used by Fiske in the main corresponded quite closely with those used by Cattell. Some similarities can be noted between the Cattell and Fiske factors, but it is difficult to tell whether the differences observed are a function of divergent extraction and rotational philosophies, the nature of the samples rated, the nature of the rater groups, or the omission of 13 of the trait variables from the Fiske study. Attempts to compare the results of either the Fiske or Cattell analyses with those found by other investigators are generally futile, since it is rarely possible to determine from the studies whether all, some, or for that matter, any of the variables used are similar from one study to another. When what might be recurrent factors are found (e.g., Extroversion-Introversion, Emotionality-Stability, and Conformity-Independence), differences in the nature of variables identifying these factors are such as to make impossible any but subjective judgments as to their possible similarities.

Norman, W. T. (1963). Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality ratings. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(6), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040291

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x

Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014996

Some years ago the Myers-Briggs personality test was popular among my peers. You can look it up, but it has introversion versus extraversion, intuitive versus sensing, thinking versus feeling as a basis for decisions, and perceiving versus judging (the latter likes to finish things up rather than hold them open). You'd get a "type" score like INTJ or ESFJ, of which there were 16 possibilities. But what I realized is that just about every human trait except for biological sex (highly bimodal) is going to be distributed on a bell curve, with most people pretty much in the middle. But "in the middle" wasn't one of the options. Myers-Briggs was useful in thinking about ways that people can be different without one being wrong. I'm pretty sure it was not validated and so thrown out like many others in favor of the Big Five model. But even on those big 5, wouldn't it be strange if they were not normally distributed too? That's not to say they're not useful because of course a significant number of people do stray significantly from the mean, and there may be interesting correlations. I just have an intuition that the answer "you're right in the middle on introversion/extraversion" or any other trait isn't what people are expecting to hear. (?).

I don't know if you're already familiar with it, but trying to look at worldviews in a dimensional way may have some overlap with the "primal world beliefs" model being researched by Jer Clifton: https://myprimals.com/