Mis-Representation

You'll have to work twice as hard to get half as far... unless you're hot!

A friend once sent me an article highlighting the miniscule percentage of Venture Capital funding going to women (2-3%). The article’s implication (which my friend echoed) was clear - female founders face a challenging path to success relative to their male peers. Yet, when I clicked through to the study the article referenced, the data painted a different picture, if it painted a picture at all.

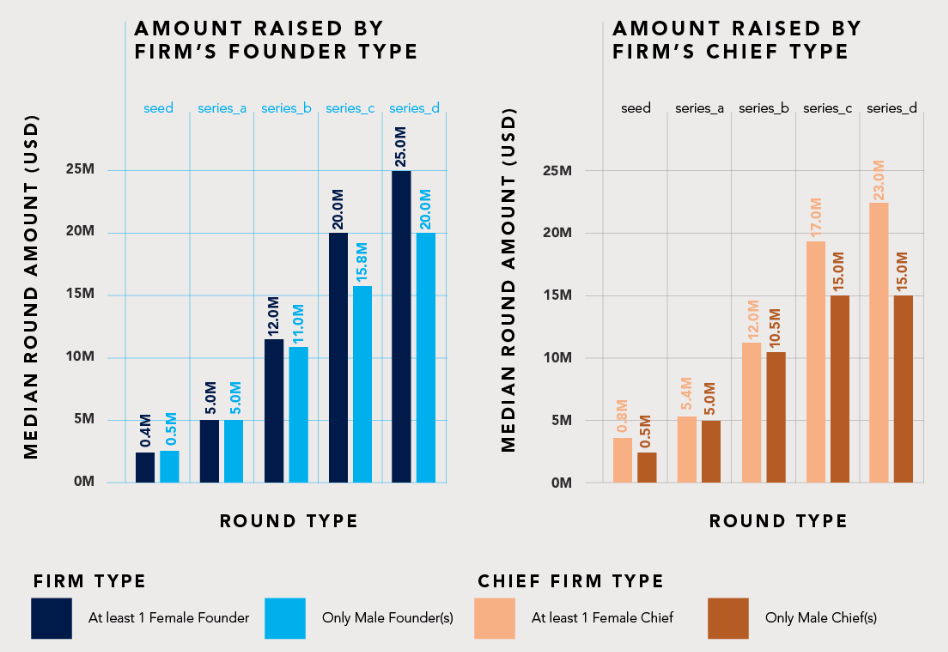

Female founders received a small proportion of total VC funding. True. However, of the firms that successfully raised VC funding, those with at least one woman on the founding team raised more on average, especially in later rounds. Neither the former “discouraging” statistic nor the latter “encouraging” one is particularly helpful for a would-be female founder. The relevant questions for her are: Out of all the women that seek VC funding, how many end up getting funded? And, are they more or less likely to get funded than men? Without those base rates she can’t know if the tiny percentage of funding going to women is a sign of gendered discrimination by Venture Capitalists or the result of very few women seeking funding in the first place.

At best, sloppy reporting of this sort of data draws unfounded conclusions from the information available and at worst, risks misdiagnosing the causes of underrepresentation, leading to a misdirection of attention and resources. For instance, the tech industry is constantly called out for its bro culture, with the implication that misogyny within tech companies is responsible for the lack of female representation. I’ve seen the ~25% female representation in tech jobs contrasted with the ~50% representation in the overall workforce when the more relevant comparison is the 19% of comp-sci degrees and 35% of overall STEM degrees which are held by women.

I’m not claiming that tech culture is as welcoming and safe for women as it can be - it probably isn’t. But the percentage of women working in tech isn’t sufficient to make or refute that claim. While workplace culture may contribute to fewer women in tech, the steepest drop off occurs much earlier in the pipeline, which is why organizations like Girls Who Code focus on supporting college age women and middle to high school age girls who are interested in STEM. Complaining about tech companies which, while not perfect, are arguably home to some of the most flexible and progressive office environments doesn’t seem likely to move the needle.

In addition to misdirecting attention and resources, presenting this sort of information without sufficient context could encourage choices which actually reify the status quo rather than challenge it. Women already tend to be less risk tolerant than men, for instance they’re more likely to skip a job application if they don’t have all the relevant qualifications. Implying that they’ll have to work twice as hard to get half as far in an industry (mainly on the grounds that it employs mostly men) does not seem likely to encourage them to enter it.

Missing base rates is only one species of this problem. Discussions which unreasonably assume causation from correlation or which ignore important opportunity costs in the analysis can be just as unhelpful. For instance, a few people have sent me this Economist article subtitled “It is economically rational for ambitious women to try as hard as possible to be thin” (emphasis mine). The article outlines the correlation between body size and income - which is clearly negative for women but only very weakly (if at all) negative for men - and states that “the fiction that clever and ambitious women, who can measure their worth in the labour market on the basis of their intelligence or education, need pay no attention to their figure, is difficult to maintain upon examination of the evidence on how their weight interacts with their wages or income.”.

While I find it plausible that larger women are on the receiving end of workplace bias and discrimination, this is one of many possible explanations for the data. It’s just as plausible that there’s a missing variable. For example, both corporate success and adherence to socially accepted beauty standards might correlate with personality traits associated with conformism. And, even if we have clear evidence of discrimination based on body size, I don’t think trying “as hard as possible” to be thin is likely to be the most “rational” response for most women. It’s just not great from a cost-benefit perspective given that losing weight takes a lot of physical and psychic energy. Energy which could alternatively be used to improve work-related skills and relationships or to put in longer hours. Moreover, pragmatic considerations aside, publications should think twice before advocating that women must actively conform to norms which oppress us as a class in order to succeed as individuals.

In addition to telling women they better get on the treadmill if they want a promotion you can find a variety of articles like this one: Up the Career Ladder, Lipstick in Hand which starts off with the following “WANT more respect, trust and affection from your co-workers? Wearing makeup — but not gobs of Gaga-conspicuous makeup — apparently can help.”. The referenced study looked at how respondent’s immediate impressions of women were related to the amount of makeup they were wearing. I’ll leave it to you to judge how confident we should be that those results will map onto how we form long-term judgments of coworkers. And again, the potential benefit of focusing on your superficial appearance is presented absent of its costs. Wearing makeup everyday is a drain on time which might’ve been put to even better use than making your coworkers think you’re pretty.

I have no problem with collecting data on gender representation or researching the degree to which superficial characteristics affect probability of success in various domains. But we can’t assume that underrepresentation is always a sign of discrimination, and we should be aware that advertising discrimination where it doesn’t exist has real downsides. I’m certainly aware that we exist in a culture that places a lot of value on female beauty. But we shouldn’t use weak evidence about how women’s looks affect their perception in the workplace to promote anti-feminist and individualistic solutions. So, what should women do to succeed in their careers? I’d guess that improving job-relevant skills, not going on a diet, is the right place to start.

It’s a typical chicken and egg situation where we need more women leaders / mentors for other women. Women leaders can serve as advocates for gender diversity and help women colleagues navigate the unique challenges of the tech industry.

The VC data that you bring up raises the interesting question of why gender integration is successful there. Maybe it points to a greater diversity of opinions and feedback leading to better pitches for funding.