It's like nobody wants to give birth these days...

Will it be childless cat ladies or spoiled single children who define our future fertility?

Recently, משכיל בינה published an article claiming that Israel’s outlier high fertility is not explained by nationalism, religiosity or natalist government policy. Instead he suggests it results from the unique way in which Israel's high fertility subculture, the Charedim, influence slightly less religiously conservative “orbiter communities” who “draw religious inspiration from” them. These orbiter communities in turn influence the broader community, transferring higher fertility norms through concentric circles of religiosity, eventually reaching even secular communities. The key, he says, is that the Charedim orbiter groups “provide a one-way channel of influence between Israeli Charedim and the rest of Charedi society, a sort of valve in which Charedi fertility memes can spread outwards, without allowing fertility decreasing memes inwards.” I find this plausible, although difficult to test, but think his more general observation, that family size decisions are “socially recursive” is likely right. As he says:

[P]eople decide to have x number of kids based on looking around at how many kids the people around them have, who in turn have that many because they looked around at how many kids the people around them were having.

If the influence via concentric circles theory is correct, perhaps the rise of rationalist trad wannabes, influenced by the Amish (?) or whatever, will spread fertility increasing memes outward through the tech bros and into the greater beyond. We shall see. However, he also makes a throwaway comment, which I’ve seen elsewhere, that decreasing fertility is primarily driven by rising childlessness:

[D]eclining fertility across the developed world is not principally, and perhaps not even at all, a consequence of smaller family sizes, but of a large and growing proportion of the population having no children at all.

It’s true that childlessness among younger women has been increasing significantly in recent years, but we don’t yet know exactly how this will translate into eventual childlessness. If we look at completed (or close enough to completed) fertility rates by tracking the average number of children among women in the 40-44 year age bracket over time we can see that there was a big decrease in average family sizes from the mid-70s to the early 90s as well as an increase in percent childless:

Historical Table 2. Distribution of Women Age 40 to 50 by Number of Children Ever Born and Marital Status: Selected Years, 1970 to 2022 from U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Fertility of Women in the United States: 2022.

TFR data from the World Bank: Fertility rate, total (births per woman) - United States.

I included the total fertility rate (TFR) above for context, but should note that completed fertility is different from TFR. The TFR provides a snapshot of fertility at a particular moment in time while completed fertility tells us about family sizes for a particular age cohort of women. TFR is calculated by taking the number of babies born per 1000 women grouped by mother’s age, averaging those fertility rates, and then multiplying that by the number of total fertile years. This attempts to normalize total fertility rates for different age distributions in the population, but it doesn’t normalize for shifts in the age at which mothers are giving birth. Completed fertility is backward looking and measures the average family size among an age cohort which is done (or nearly done) with having children.

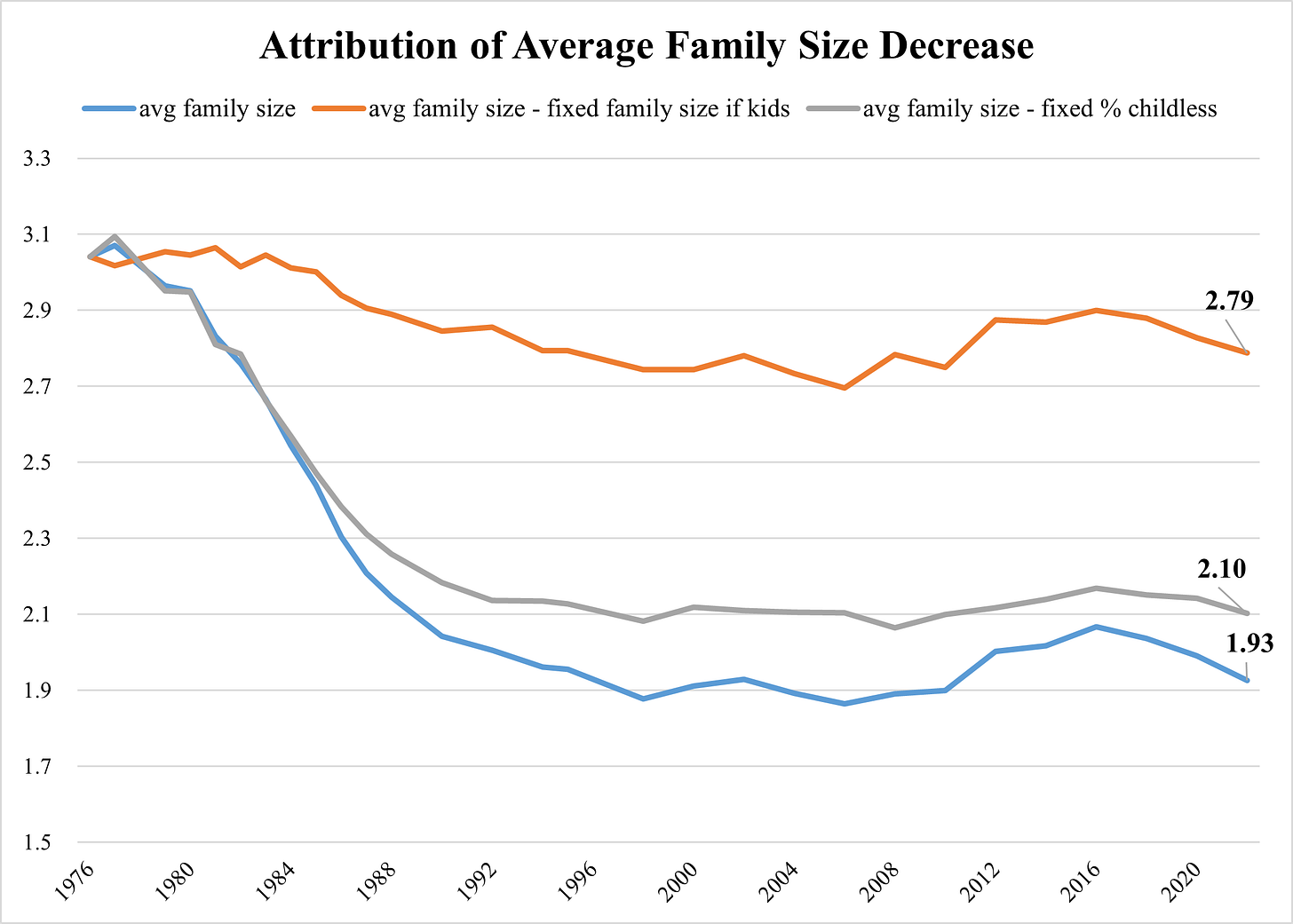

Looking at completed fertility, we can ask what drove the decline from the mid-70s to the early 90s: Was it mainly that more people had 0 children or that those families that had children had fewer of them? Well, in 1976 the average number of children among women 40-44 who had at least one child was 3.39 and 10.2% of women in this cohort were childless. In 2022 the average number of children among women 40-44 who had at least one child was 2.34 and 17.7% of women in this cohort were childless. We can ask what the average completed family size would’ve been had average family size in families with at least one kid stayed at it’s 1976 level while childlessness increased vs. if childlessness stayed at it’s 1976 level while average family size in families with at least one kid decreased. This allows us to get a sense of the attribution to each factor, both of which contributed to lower completed fertility.

As you can see from the above chart, keeping completed average family size among families with kids fixed at the 1976 level would’ve kept completed fertility much higher than fixing childlessness at 10% would have - about 80% of the decline in completed fertility over this period is attributable to smaller family sizes among families that had kids while about 20% is attributable to higher rates of childlessness. Getting the childless rate back down to 10% would help a lot but not nearly as much as increasing the fertility rate in families that have kids back to the 1976 level of 3.3. I’m not saying that’s realistic, but I am saying that higher childlessness has not been the main driver of lower fertility so far.

But as I already said, this is just a backward looking metric. What people are really worried about is the alarmingly high childless rates among women in their 20s and 30s in cohorts born after ~1980:

Historical Table 1. Percent Childless and Births per 1,000 Women in the Last 12 Months: Selected Years, 1976 to 2022, from U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Fertility of Women in the United States: 2022.

But many of us childless cat ladies in our 30s are still very much planning to have kids! And many of us are also on track to do so. Women who get married under 28 in New York are basically considered to be child brides, so being childless at 30-34 is completely normal in my social context, even though more or less everyone I know wants kids. Projecting what the childless rate will be when my cohort completes fertility is therefore a bit tough - it’s unclear to what degree the current childlessness rate reflects a decision to delay rather than forgo childbearing and to what degree improved reproductive technology will enable this desired later fertility. While I think it’s important for women to be aware of their fertility window and also think that more women should engage in fertility preservation (assuming they have the means), we should also keep in mind that for families who want only one or two kids - which is most families - starting in your 30s is generally early enough (barring complications that require large spacings between pregnancies or other issues). This is especially true if, as is the case with several couples I know, they’d like two kids ideally but would also be happy with just one.

Ruxandra Teslo also referred to this childlessness data in her piece on cultural trends and fertility, pointing out the observation mentioned above, that childlessness has increased among the cohorts of women who have yet to complete their fertile years relative to older cohorts of women when they were the same age:

[S]o far early-in-life childlessness has been a very good predictor of late-in-life childlessness, so one can make some inferences about the future. Applying this logic, demographer Lyman Stone forecasts a precipitous rise in the rate of childlessness among American women born after 1984. For women born in 1992, he projects a childlessness rate of more than 25% at the end of their reproductive span. [...] If Lyman’s analysis holds true, we might be transitioning into an era of both small family sizes AND a relatively high childlessness rate. Of course, one has to bear in mind these are just projections. Many things can happen while women in younger cohorts are still able to bear children: maybe these women will behave completely differently from those in older generations, breaking the assumed correlation between fertility at younger ages and total realised fertility. Maybe we will see a large cultural shift before these women reach the end of their reproductive span. Or maybe we will dramatically alter reproductive span, allowing women to have children later on in life — the solution I hope for.

I think we have at least some reasons to be hopeful that childlessness rates will decline more than expected, and that the women in my cohort will to some degree break “the assumed correlation between fertility at younger ages and total realised fertility”, particularly if reproductive tech improves in the meantime. So I decided to take a look at childlessness rates historically in order to estimate expected completed childlessness for my cohort using a couple of different methods. But first, I’ll quickly go over the anecdata that’s leading me to feel relatively optimistic about my cohort’s childlessness rates.

Almost all the women I know who are currently 30-34 will very likely have kids eventually:

Going through my personal rolodex of 11 female friends in this age bracket plus myself, 50% have kids already. Of those who don’t have kids, five out of the six want to, and four of those five are on track to do so within the next few years. Only one of my friends does not plan to have children, and she’s still open to changing her mind. Of those who do have kids already, three have one, two have two and one has five. (Yes, that’s right, one of my girlfriends is a literal Ballerina Farms, down to the size 2 dress size and aspirational family portraits.) All of my friends who have one expect they’ll likely have two but don’t necessarily have a strict plan in place to do so and are open to having just one. Only one of them (me) has done fertility preservation (as far as I know), but as I’ve said most of them don’t expect to need it since they only want two kids max and most would be fine with one. What I do think is likely, is that some of my friends who may have hypothetically wanted two children will stop at one, possibly as a result of delayed timing or difficulty. But my personal observations make me hopeful that what we’re seeing is another shift towards later births and that childlessness will rise less than some historical relationships would suggest.

Percentage of first births that are to women over 35 has increased… but not very much:

However, as Lyman points out in his analysis, there’s limited evidence that higher childlessness among women in their 30s is purely the result of delaying the age at which they have their first child. As he says:

Declines in first births have been very large and extend all the way up to women in their mid-thirties. Meanwhile, there have not been appreciable increases in first birth rates among women in their late thirties and into their forties. Lost first births at younger years are not being made up in later years. The argument that childless women are going to “catch up” and that the share of women who are childless will not rise in the future is almost certainly wrong.

To see what Lyman’s getting at I plotted the percentage of first births in a given year to women over 35, and as he said, it has increased but not dramatically so:

Data from CDC Wonder. I compiled Natality information for 2003-2006 and 2007-2022 by pulling birth data grouped by mother’s age and live birth order for each year.

As of 2022, 38% of women 30-34 were childless and 12.3% of first births were to women over 35 vs. just over 8% a decade earlier. The percentage of first births to women over 35 has been increasing over the past decade and I’d expect that to continue. Linearly extrapolating from the 10 year average increase in percentage of first births to women over 35 yields a projected 16.6% of first births to women over 35 by 2032. But even if we assume that 16.6% of eventual mothers in the 30-34 years old cohort as of 2022 are yet to have kids, that would still imply a completed childlessness rate of 25.7%, slightly higher than Lyman’s 25% figure. If the percentage of first births over 35 ends up being lower, staying at the current 12% level however that would imply eventual childlessness rates of 29%!

If the increase in percentage of first births to women over 35 began increasing at twice the linear rate over the past 10 years we’d end up with 21% of first births to women over 35 by 2032. And if we assumed that 21% of eventual mothers in the 30-34 years old cohort as of 2022 are yet to have kids, that would imply a completed childlessness rate of 22%. So, unless we see the percentage of first births to older women start to increase at a minimum of double the rate we’ve seen over the past decade we are on track for something like the 25% childlessness rates that Lyman projects.

But… the motherhood “conversion ratio” has increased and could potentially rise further:

Looking at the data on childlessness since the mid-70s, I considered what percentage of women who were childless at 30-34 had children by the time they were 40-44 by comparing the childlessness rates between these two cohorts with a 10 year lag:

Historical Table 1. Percent Childless and Births per 1,000 Women in the Last 12 Months: Selected Years, 1976 to 2022, from U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Fertility of Women in the United States: 2022.

This “conversion rate” rose sharply from around 25% in the 90s and early 2000s to around 45% in the 2010s. The latest data point from 2022 showed a decrease to 37% from 44% in 2020 - it’s unclear if that is the beginning of a shift lower, but I’d doubt it given trends (which Lyman also identifies) of later marriage, later job stability etc. which predict a rise in later first births not to mention better reproductive tech and better outcomes for older mothers. The 25% projection Lyman referred to would imply a conversion rate of only 34% (given current childlessness of 38% among women 30-34), which I think is a little pessimistic, at least unless the 2022 number was actually the start of a trend. If instead 45% end up converting, as was the case through the 2010s, we’d end up with 21% childlessness, still a significant increase from 17.7% in the latest completed cohort but much lower than the 25%+ predicted above. This 21% childlessness would require something like a doubling in the rate of increase to the percentage of mothers having their first child over 35, as discussed above.

Perhaps I have a skewed perspective but my anecdata leads me to predict that the “motherhood conversion rate” for my cohort will be at least as high as it’s been over the past decade. And if it went even higher, say 50% we’d end up with only 19% completed childlessness. While the trend over the past decade in percentage of first births to women over 35 still predicts high completed childlessness (25+%), I’d predict that the percentage of first births to older moms will begin increasing at a faster rate as women like myself begin having children. I may be too optimistic, but if I had to give a number I’d estimate an eventual childlessness rate of around 22% which implies 21% of those mothers will start after 35. But if many mothers in my cohort will have their first child quite late, some of those mothers may not have time to have a second or third child, even if they hypothetically would have wanted to.

I think smaller family sizes are likely to be almost as important to future fertility as increased childlessness

I think the average family size among women with kids is likely to decline (after being roughly stable since the 90s) and could therefore be a primary driver of changes in completed average fertility for my cohort. Women are pushing out fertility into their later years by choice, but fertility preservation, while growing, remains niche and I therefore think we could see a rise in single child families, similar to the rise we saw from the early 80s to the early 90s. And if family size decisions are socially recursive as משכיל בינה suggests, this could also lead to a rise in the percentage of families in younger cohorts that intend to have only one child regardless of time constraints.

Historical Table 2. Distribution of Women Age 40 to 50 by Number of Children Ever Born and Marital Status: Selected Years, 1970 to 2022 from U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Fertility of Women in the United States: 2022.

I wasn’t able to find great data for the typical number of children born to women who had their first birth over 35, but I’d expect these women tend to have significantly smaller families. This report indicates that is in fact the case, as they found that among women who had a birth between 2015 and 2019 “[t]he percentage of women who did not have a second birth increased with older age at first birth. For example, 47.5% of women aged 30–49 at the time of their first birth did not have a second birth compared with 26.6% of women aged 20–24 at their first birth.” Of course some of these women would have gone on to have additional children after the survey period, but they were also looking at women who had their first birth after 30 rather than after 35. So let’s assume that for women who start over 35, about half will have only one child. In that case, we’d assume the average family size for women who have their first birth after 35 is around 1.5 kids.

Among women who were 40-44 in 2022 and had children, their average number of kids was 2.34. And if something like 11% of these women had their first child after 35 (which was the percentage in 2019, when this cohort would’ve been 37-41) and that those women who started “late” had 1.5 kids on average, this would imply that women who started having kids before 35 had something like 2.45 on average.

Keeping the average number of kids among women who start before and after 35 fixed, an increase from 11% to 21% of mothers starting families “late” would reduce average family sizes among women with children from 2.34 to 2.25. And if childlessness remained fixed at 17.7% this would imply average family sizes of 1.85 vs. 1.93 currently, based only on the increase in single child families. If, alternatively, average family sizes among families with kids remained fixed at 2.34 and childlessness increased to 22% this would imply average family sizes of 1.83 vs. 1.93 currently. So these could be similarly large downside risks to overall completed fertility.

If the average family size among families with kids decreased to 2.25 and childlessness increased to 22%, as I expect, this would imply an average completed family size of 1.76 which would be the same average completed family size we’d get if family sizes among families with kids remained stable but childlessness increased to 25%. So, I get to the same place in terms of expected completed fertility as Lyman likely gets to, but I think almost half of the decline will be caused by more single child families and the rest will come from higher rates of childlessness.

I think we can do more to increase family sizes than we can to reduce childlessness

My concern is that with more moms starting late, single child families will become more normal. And if the socially recursive method of determining ideal family sizes is correct, this could lead to sustained lower fertility in future cohorts, including among women who start having kids earlier. As single child families become more normal families with three or more kids become more weird. Even now, most parents I know think three kids is slightly “crazy” and a friend of mine who’s a few years older than me with two kids has observed that because so few families have three, those that do can face mild social disadvantages - for example she’s noticed that parents with only one or two kids are less excited to host a playdate where they’d have to care for someone else’s three kids.

In terms of what we can do to change these trends, I think creating cultural or policy based incentives which motivate people who would otherwise have ended up childless to have kids would be significantly more “expensive” than incentives which would motivate families who would otherwise have had one or two kids to have two or three kids instead. I argued about this briefly with Bryan Caplan when he came on Moral Mayhem and I explain my view in detail here. He has suggested a policy which gives tax breaks to parents and where the largest marginal benefit comes after a couple has their first child. This approach is based on the belief that incentivizing people to have their first child is high leverage because if you can get someone to have one kid then they’ll very likely end up having two. This is a good point, but less so if more women are having their first child in their late 30s and haven’t done any fertility preservation, and less so again if more people start to see a single child family as ideal.

In addition, 10% has been sort of the “minimum” childlessness rate in recent history. So if we’re expecting a rise from the current 17.7% childless to something in the 19-26% range, how much do we really think we can bring that down? Maybe we could lower it to 15%... but that would mean that any policy that gives parents financial incentives to have their first kid would be mostly going to families who would have had that baby anyways. This is why I think any fertility policy should focus on incentivizing the third and higher order children, as I explained in Can we afford to buy marginal babies?:

I think we should not bother paying for first babies since attempting to economically incentivize would-be childless women to have kids would be the least cost effective for a few reasons:

Most women (~75%) are expected to have at least one baby and given the past childlessness rates I’d expect that at best we could increase that to around 85%. This means that at most 12% of first babies could be expected to be marginal, so you’d mostly be paying for babies that would’ve been born anyways.

Childless women seem more likely to have other non-economic factors preventing them from having babies. For example, it’s likely much more difficult to incentivize a woman to have a baby if she doesn’t have a good, stable partner.

And lingering on the second point, people who are childless in their 20s or early 30s are generally childless for reasons. As I said in Young Mom Old Mom:

While I don’t disagree that subsidizing young women having kids could be part of the solution, I’m not sure how effective it would be. Or put another way how expensive it would have to be to be effective. At least among the women I know (yes, mostly college educated) most just weren’t ready to have kids in their 20s due to some combination of the following reasons:

They hadn’t found a stable relationship yet

Hadn’t achieved financial stability

Were attempting to advance in their career in a way that was incompatible with having young kids (junior roles in most industries in North America come with the expectation that you’re ready and able to work late etc.)

They just didn’t want kids yet and were enjoying their extended adolescence

So, I agree with Lyman that rising childlessness is likely to be a major problem for overall fertility - but I think childlessness will end up lower for my cohort than he’s currently forecasting while also expecting average family size (among families with kids) to decrease more than it has in the past few decades. I think the end point in terms of predicted completed fertility will be roughly the same, but the implications for how we ought to incentivize fertility are different. I do think we’re witnessing a shift to later births and that therefore what can be will, more or less, be unburdened by what has been.

In summary I think that we will see more women my age and younger starting families late, and that therefore the childlessness rate will rise somewhat less than historical relationships might lead you to expect. But also, that absent any additional fertility incentives, family sizes will get smaller on average. The socially recursive nature of fertility decisions and the barriers to having your first vs. having additional children lead me to conclude that policy which provides financial incentives for fertility will be more efficient and effective if focused on encouraging larger families rather than on discouraging childlessness.

Cross-posted from Twitter:

I’ve heard several other people report similar things about what their friends are planning. I think you’re on to something.

At the same time, there are two major caveats as to what your observations imply about overall fertility:

One: sorting. Other people’s “observations of friends” have produced very different averages. In the linked thread, many people report <1.0TFR averages, even >35yo.

People who want kids (or don’t) tend to disproportionately make friends with each other.

Two: the “friendship paradox”. Your friends very likely have more friends than the average person, because if they didn’t have friends, they wouldn’t be your friend!

And we know that people with fewer friends are less likely to get married or have kids. So “observations of friends” are likely to systematically overestimate fertility.

I’m curious if you have data on a cohort that is _not_ selected (e.g. a plausibly random sample of your high school classmates).

Another thing I’ve heard some other people who work on this propose for the college educated class, is shortening the length of college degrees by a year or two.

The current 4 year college pathway means you enter the workforce in your mid-twenties and will end up being financially stable only in your early thirties.

If the time to attain those qualifications was shortened a bit, you could enter the workforce in your early 20s and have the same duration of time earning money and as a result become financially stable in your late 20s instead. Which could be a potential sweet spot where you’re still highly fertile and now financially stable.

Also gives some more time to people at that stage of their career to date more if they haven’t already since women in their early 30s stress out but if they were in their late 20s instead but still in the same financial position, they could vet men better and date better too.