The Myth of Personal Style

Are we all really just some genre of basic?

In a recent video Youtuber and fashion blogger Mina Le noted that “over the past 10 years looking or being basic has morphed into this major insult”. But, she asks “why is it so bad to have the same taste as the majority?” Now, I’m not so sure that “being basic” is newly insulting. The specific word might be novel, but excessive conformism has always been seen as less than positive within subcultures that value creativity.

Still, when I was in high school “basic” wouldn’t have been much of a “burn”. The popular girls were wearing Abercrombie and Fitch. No one was boiling over with jealousy at your “cool vintage clothes and vacation photos”. Thrifting was not a marker of your commitment to sustainability and original style… it just implied you were poor. And conformity was in during my university days as well1—it felt like every other girl on campus had been given a winter uniform along with their tuition dues: Hunter boots (with the cute cable knit socks), Canada Goose jacket, maybe an infinity scarf, Lululemon yoga pants and a Longchamp tote in which to carry their Macbook and a vitamin water.

Obviously basic girls continue to sit atop many hierarchies; not all subcultures reward originality or punish conformity, just look at the DCCs who tirelessly strive to embody the archetypal cheerleader that exists in Kelli’s mind with every ‘yes ma’am’ and hip destroying jump split. Still, as Mina points out “in creative cities like New York and in online spaces” basic is an insult. But… what exactly is basic?

In Mina’s video she uses the term to refer to relatively simple outfits made up of mostly basic pieces which the majority of people would think look “good”. But I think the term has a different connotation better captured by an old comment on r/femalefashionadvice which explains that “basic” implies dressing in a way which is “trendy while not being boundary pushing or novel in any way whatsoever.” And that it involves “only deciding to wear something once it's been 110% vetted by everyone else on earth”.

The trend cycle

Trends are started by people we’ve already collectively decided are cool. These are the trendsetters—the “hot internet girls”. Most of them are attractive… but there is an oversupply of pretty girls, so it’s also “definitely a je ne sais quoi kind of situation”. When these cool people wear something most other people aren’t wearing, that thing becomes endowed with a little bit of their cool energy. People who are paying the closest attention to what the cool people are doing notice, and some of them decide to copy it because doing so makes them feel cool too.

(“I saw Regina George wearing army pants and flip flops, so I bought army pants and flip flops”)

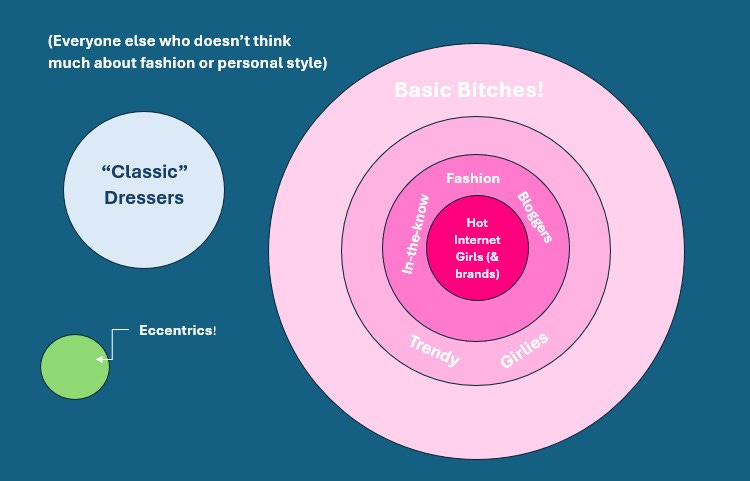

The group that begins copying the trendsetters first occupies the inner circle of trendiness right next to the trendsetters themselves. But they’re surrounded by concentric circles of trend followers who are paying successively less attention and/or are successively less willing to risk looking stupid by wearing a trend they “can’t pull off”. Most of the time the trend burns out before it reaches the masses, because a lot of trends are objectively ugly (and are seen as such in retrospect even by many of the people who participated at the time).

In fact, something being objectively ugly can be a positive for a trendsetter. A way to flex. Proclaiming to the world “Actually, I’m so cool (or hot) that I don’t even worry about presenting beautifully, I just wear whatever I find and you can’t help thinking I look good.” (See. for example: Is it a fit or is she just skinny?)

I had planned to use the ripped shirt look, which I associate with Kanye West and Justin Bieber circa 2016, as an example of a trend too ugly to have had a real shot at becoming basic… but there’s both an Urban Outfitters and a Temu version of it, so maybe it made it further than I realized. Regardless, the point is that a lot of us think that people who uncritically adopt every trend look silly, and this is a large part of why people discourage trend following—it’s expensive (and wasteful) to keep up with, and there’s a very good chance that you’ll look bad not only to your contemporaries but also to your future self.

But in some cases a trend will spread further and further out, until it’s no longer “boundary pushing or novel in any way whatsoever” because it’s been “vetted by everyone else on earth”. And at this point, those still wearing it will be advertising that they’re “basic” while the trend setters and fashion bloggers will have long ago moved on to something else. (Although these days the time it takes for a trend to go from signaling cool to signaling basic can be insanely short due to the sped up nature of trend cycles which the combined power of social media + SHEIN has enabled.) I took a shot at representing this visually below:

I set “classic” dressers apart from the concentric circles of individuals who drive the trend cycle. Of course, you can’t ignore the slower moving changes in norms of dress without just looking weird, so what’s considered classic (or “timeless”) is in reality still somewhat dependent on time and place. But I think “classic style” implies outfits that look good “objectively” or which draw on styles which have been popular for a very long time—the fact that classic and timeless are often used synonymously highlights the intuition that styles which have “stood the test of time” have generally done so because they’re objectively pleasing.

So my interpretation is that when we say an outfit is “classic” we mean that it’s in some way naturally pleasing to the human eye, using cuts and proportions which flatter the body (where “flattering” implies garments that make your body appear strong and slim and healthy) while also being context appropriate. People who promote dressing in a “classic” way often point out how this allows them to buy more expensive clothing items (they call this investing lol) which are made with higher quality materials and better techniques since they have relatively low closet turnover and often wear simpler pieces which can be incorporated into many different outfits. They also avoid the “bad trends” and so arguably look better to most people most of the time than their trendy or basic girlfriends do.

While basic is generally an insult, classic is often a compliment. The reddit comment I mentioned above, for instance, which had attempted to define basic, was in response to a post from a woman who said she dresses “classic” and “chic” but would “want to avoid "basic," obvi”. (Obvi!) And the comment also stressed that “being basic” is “not to be confused with dressing in basics which is used to describe plain, simple cuts of clothing that are usually non-distinctive and not especially detailed”.

Finally, I also set the eccentrics aside in their own little bubble (quirky probably fits there too as a toned down version of an eccentric). These people are defined specifically by wearing things which are in some way context inappropriate. They do this (I suppose) either because they have very strong preferences for what they like and those preferences just happen to be very different from those of the mainstream, or because they are especially uninterested in the opinion of others, don’t mind weird looks, and enjoy experimenting. These people often look interesting… but they don’t normally look fashionable or cool, at least not unless they’re already cool for some other reason. And it’s easy for their outfits to feel “costumey”.

Taste

But this model of the trend cycle misses something crucial to a discussion of fashion and style. Taste. Some trendsetters are themselves considered basic by people who, while they may not be as influential, nevertheless feel in a position to judge the quality of the tastemakers to the masses. Hailey Bieber comes to mind as an example of someone who’s undeniably a major trendsetter but who is a frequent target of the complaint that the “style icons” getting the most attention aren’t the ones coming up with looks that are particularly novel or interesting or beautiful.

Now, maybe you’re suspicious of the concept of taste. Maybe you think “good taste” is simply determined by (and a signal of membership within) something analogous to a high priesthood. Or maybe you think that “taste” is about more than signaling, that it refers to a “capacity for deep aesthetic pleasure, and the discernment to judge whether a given thing is capable of inducing deep aesthetic pleasure”. (Or maybe you think both are somewhat correct, they aren’t necessarily inconsistent.) Regardless, we can all agree that there are some people who are at least believed to have “good taste” and plenty of influencers who… are not.

This means that trends can catch on even if no one who’s considered to have “good taste” thinks they’re interesting or would be eager to copy them. And so trends can sometimes completely skip over the concentric circles of bloggers and ”in the know” fashion girlies to almost immediately become oversaturated and “basic”.

But “alternative” and “taste-having” subcultures also have trends and trend cycles. So how should we think about the sort of conformity you can find within subcultures whose members prize themselves on originality? Can someone be basic qua a taste-having subculture? Is the form that “basicness” takes context dependent?

Another genre of basic

A few months ago Brooke LaMantia wrote an article for the Cut about her revelation that her carefully crafted “personal style” maybe “wasn’t so personal” after all:

Last summer, my best friend and I were drinking an Aperol Spritz in Dimes Square when I noticed scores of women walking by in different iterations of the same outfit: an oversize tee, a skirt, white socks, sneakers or loafers, and some kind of embellishments in their hair. I looked down. I was wearing an oversize button-up, a maxi skirt, white Nike socks, and vintage loafers. Suddenly, everywhere I looked, I saw myself, and it felt mortifying. Who was I to think my outfits were better, or less basic, than anyone else’s?

It felt mortifying! It’s one thing to look like everyone else intentionally, but for Brooke, who had been trying her hardest to look original, realizing she looked like every other girl she’d be likely to hang out with was deeply embarrassing. Especially because she thought she had soundly escaped her previous basicness:

After I moved to the city, I spent my late teens and early 20s on a grimy block primarily occupied by college-age kids and fresh to New York young adults. I adopted their uniform: jeans, black tops, Air Force Ones (or whatever the trending sneaker was of the year), and an expensive yet uninspired purse.

(I feel attacked!) She was once basic too, but then she intentionally made a choice to try harder… so that she could appear as though she wasn’t trying: “I wanted my style to communicate that I knew what was cool, but I didn’t care too much.” But importantly, she wanted to look like she “knew what was cool” specifically within the context of her subculture, accounting for what was considered “cool” within that community.

This touches on what I was getting at in The Gaze of Your Subculture. Even if you’re not dressing for “the male gaze” almost all of us (Agnes Callard aside) are dressing for others. We’re trying to communicate something to some relevant group of people, it’s just that when what defines that relevant group is that they’re generally similar to you it can feel pretty close to “dressing for yourself”:

Fashion is a form of aesthetic expression. The act of intentionally selecting an outfit (and when I say outfit I’m including the hairstyle, makeup, accessories etc.), is a way of communicating with others through self-presentation. Constructing an initial context about who you might be or where you’re coming from before you even start an interaction, one which can’t help but be picked up on by those around you, even if only unconsciously.

By becoming “a whole other genre of basic” Brooke was very, very clearly signaling her membership in the group she wanted to signal membership within. So while it may have felt mortifying to realize it, she was actually succeeding entirely in presenting herself as she had intended, as if she “knew what was cool”. And she more or less comes to this conclusion in the piece:

What I realized was that in the age of social media, a sense of uniqueness is damn near impossible to find. And maybe it’s overrated. We are all getting our style from somewhere; why not let it be from other queer kids my age?

But there is at least one major difference between the “genre of basic” which Brooke ended up embodying and what we generally mean when we talk about someone “looking basic”. Effort. While I appreciate the self-awareness she displays when she recognizes that her harsh judgements of other’s fashion choices were mostly unfair, I’d argue that Brooke really is much more stylish than the typical basic girl.

Finding all those perfectly imperfect vintage pieces takes a lot more work (and thought) than buying out an Aritzia does. And even if you’re hostile to taste and think it’s simply about “knowing the rules” within a relevant subculture, the rules she learned were a lot more complex and difficult for outsiders to parse and recreate than the implicit rules that basic girls follow are. If you’re a little more sympathetic to taste you might also think that Brooke’s closet building journey encouraged her to develop a deeper ability to appreciate fashion such that it could better “induce deep aesthetic pleasure”. After all, she probably wouldn’t have gotten so into it if she wasn’t enjoying this outlet for self-expression.

We tend to praise originality as if it’s something all of us should be aiming at but, as I mentioned above, people who dress in a really original way don’t typically look like fashion icons, they just look… eccentric. To be fashionable requires you to be present in the here and now. To understand the cultural signals you’re putting out and how they’ll be received in the relevant context. Because again, style is a form of communication.

Dressing super eccentric is sort of like walking into the bar, seeing your friend and being like “smok agay dau?” rather than saying “hey, how you doing?” simply because you thought it sounded better and didn’t mind being weird. But everyone else is like… ok that’s fine, you do you girl(!) just know that we don’t know what you’re trying to say and you probably aren’t being perceived as intended!

So my conclusion is something like… to be considered fashionable and stylish (as a normal person, not as someone whose job is fashion) you pretty much need to conform to some genre of basic or else dress mostly in classic, timeless pieces, whatever that might look like in your specific environment2.

I had planned to discuss Mina Le’s video more in this piece and I also wanted to reference some of derek guy’s commentary on twitter… but this is getting long. So for now, you can just enjoy these pictures of Mina and accept that originality is mostly overrated for the other 99% of us.

At Queen’s University from 2010 to 2014

Of course there’s still a lot of variety within that: you can dress classic while playing with color, you can add unique accessories which differentiate your basic look etc. etc. etc. And many of us don’t exist within a subculture which has such a well defined but narrow aesthetic as Brooke’s did.

On the subject on trendsetters, have you read this Louise Perry article?: https://open.substack.com/pub/louiseperry/p/transgenderism-is-over?r=2fkpru&utm_medium=ios

This is allegory for culture and idea propagation more generally, right?